Third Country Deportations Tracker

This page is a public resource that compiles publicly available information to document third country deportations from the United States. If you believe we’re missing information, would like to suggest additional areas for coverage, or have questions for our team, please contact us below.

Last updated: December 12, 2025

This tracker currently covers third country deportations to countries in Africa and Asia.

Jump to: Countries in Africa | Countries in Asia | Responses

Intro

Third country deportations are deportations of an individual to a country that is not their country of nationality or their last country of habitual residence. Since February 2025, third country deportations have been systematically pursued as an immigration enforcement tool in the United States. The practice often results in torture, cruel treatment, arbitrary detention, and other serious human rights abuses.

The U.S. scheme is not the only third country deportation scheme proposed or in place around the world. However, it is distinct in several ways, from the lack of advance notice provided to noncitizens prior to deportation, denial of a meaningful opportunity to challenge the deportation, to the withdrawal of responsibility of the individual post-deportation. The United States is also deporting people with humanitarian-based protections in direct contravention to both U.S. and international law.

The Agreements: The Executive Branch has pursued agreements with numerous countries to accept third country deportees. In exchange for accepting non-nationals, foreign governments have in return received money, visa restriction lifts, and other favorable treatment from high level officials in government. Most of these agreements are not made public.

Taken from U.S. Soil: Those subject to third country deportation are individuals who have been arrested by U.S. immigration enforcement from their homes, communities, or jobs. Others have been arrested when they showed up for mandatory U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) check-ins or court hearings. Some were in immigration detention, which is another immigration enforcement tool that has been used increasingly been used illegally to detain people without reasonable suspicion.

In many cases, individuals do not receive notice of their deportation or their final destination country before being boarded onto a flight. If individuals receive notice, it is usually in English, even if the individual cannot understand the language. Individuals subject to third country deportation typically have no choice in where they are sent, a practice that raises serious due process and human rights concerns, particularly when the receiving country may not be safe. Flights leaving the United States may stop in transit on U.S. occupied soil or another country before arriving in the country that agreed to accept third country deportees.

Landing in an Unfamiliar Country: In almost every case, individuals have no ties to the third country. It is neither their country of nationality nor the country where they last resided. It may even be their first time on the continent.

Upon landing, the individuals are subject to the laws and policies of the third country. Once individuals leave U.S. airspace, the United States withdraws all responsibility. In a third country, individuals are at increased risk of chain refoulement, or removing a noncitizen to a third country who then removes the noncitizen to a country where they face risk of harm, torture, or persecution. The third country may have already started the process of facilitating their voluntary or forced returns to their country of origin. In some cases, the third country may not have strong diplomatic ties with a deported individual’s country of origin, further complicating the individual’s return.

In the meantime, individuals have been forcibly detained in airports, prisons, and military camps in the countries in which they have been deported. Although many of the countries have laws for refugees and asylum seekers, those rights do not seem to be afforded to individuals who may be forcibly returned to a country where they fear persecution or torture without notice and without a meaningful opportunity to challenge the return.

Legality: While the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) and other U.S. law does not absolutely prohibit third country deportations, there are safeguards that the U.S. federal government must follow. Deporting any noncitizen to a place where their life or freedom would be threatened violates domestic and international law. Deporting certain humanitarian immigrants, including refugees and asylees, disregards the protections Congress intended when it passed the Refugee Act of 1980.

The below chart outlines U.S. law around third country deportations for certain categories of noncitizens.

Chart 1. U.S. Law on Third Country Deportations

| Noncitizen Category | Third Country Deportations |

|---|---|

| Applies to all of the categories below |

Before any removal, constitutional guarantees and safeguards must be afforded to noncitizens. The United States may not remove noncitizens to any country where their life or freedom would be threatened because of their race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. The United States may not remove noncitizens to a country where they would be tortured.

Sources: 8 U.S.C. § 1231(b)(3); 28 C.F.R. § 200.1 |

| Asylum Applicant |

May be sent to a “safe third country,” pursuant to a diplomatic agreement with assurances that the individual’s life or freedom would not be threatened on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. Once deported, the individual would have access to claim asylum or equivalent temporary protection in that country. The United States has had a safe third country agreement with Canada since 2002. Recently, new agreements have been signed with countries around the world. Jump to section “Asylum Cooperative Agreements.”

Source: 8 U.S.C. § 1158(a)(2)(A) |

| Asylee (Asylum Granted) |

Third country deportations are not allowed before a formal termination of asylum status is final. A grant of asylum is for an indefinite period of time. An asylee is authorized to stay and work in the United States. An asylee is eligible to apply for a green card after one year of residence in the United States. Sources: 8 C.F.R. 1208.14(e); 8 U.S.C. § 1158(c)(1) |

| Asylee Grant Terminated |

In order for an asylee to be deported, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) must pursue a formal termination of asylum status. There must be a reason for termination, such as a fundamental change in country conditions or the asylee is a danger to national security. DHS must provide adequate notice of a request to reopen a case in immigration court. An immigration judge must exercise their discretion in granting the motion to reopen. During the proceedings, the asylee is granted the right to be represented. If an immigration judge finds sufficient grounds for termination, the individual may be removed to a third country pursuant to a diplomatic agreement with assurances that the individual’s life or freedom would not be threatened on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. The individual must be eligible to receive asylum or equivalent temporary protection in the third country.

Source: 8 U.S.C. § 1158(c)(2) |

| Withholding of removal |

A grant of withholding of removal does not afford an individual the level of permanency or family reunification as asylum. A grant of this status means that the individual cannot be returned to their country of nationality or place of last residence where their life or freedom would be threatened. Multiple courts have held that noncitizens cannot be removed to a country that was not designated by an immigration judge as a possible country for removal. In order to propose another country for removal, proper notice and an opportunity to be heard must be afforded to the noncitizen. In order to ensure compliance with the Convention against Torture (CAT), of which the United States is a signatory, the Secretary of State must receive assurances from the country’s government that a noncitizen would not be tortured. The Secretary must ensure that assurances are sufficient enough that the deportation would be consistent with Article 3 of the CAT. Sources: 8 U.S.C. § 1231(b)(3); 8 C.F.R. §§ 1208.16(f), 1208.17(a); 28 C.F.R. § 200.1; Andriasian v. INS, 180 F.3d 1033, 1041 (9th Cir. 1999); Kossov v. INS, 132 F.3d 405, 408-09 (7th Cir. 1998); El Himri v. Ashcroft, 378 F.3d 932, 938 (9th Cir. 2004); Aden v. Nielsen, 409 F. Supp. 3d 998, 1004 (W.D. Wash. 2019) |

| Convention against Torture (CAT) relief |

A grant of relief under CAT does not afford an individual the level of permanency or family reunification as asylum. An individual could be granted withholding of removal or deferral of removal under CAT. DHS must seek a formal termination of this status before removing a noncitizen through filing a motion, providing notice, and a hearing. The noncitizen must have an opportunity to submit additional evidence. The immigration judge must make a de novo determination as to whether the noncitizen’s case warrants CAT relief. In order to remove an individual to a third country, the Secretary of State must receive assurances from the country’s government that a noncitizen would not be tortured. The Secretary must ensure that assurances are sufficient enough that the deportation would be consistent with Article 3 of the CAT.

Sources: 8 U.S.C. § 1231(b)(3); |

| Any other noncitizen ordered removed |

For any other noncitizen ordered removed, immigration officials must first allow the noncitizen to designate a country for removal. The Attorney General cannot ignore the noncitizen’s designation, unless they fail to designate a country promptly, the designated country refuses to accept the noncitizen, or removal to the designated country would be prejudicial to the United States. After exhausting the possibility of removal to the designated country, a noncitizen may be removed to an alternative country, including:

After exhausting those options, a noncitizen may be removed to another country that will accept the noncitizen. Sources: 8 U.S.C. §§ 1231(b)(2)(E), (b)(3)

|

Countries in Africa

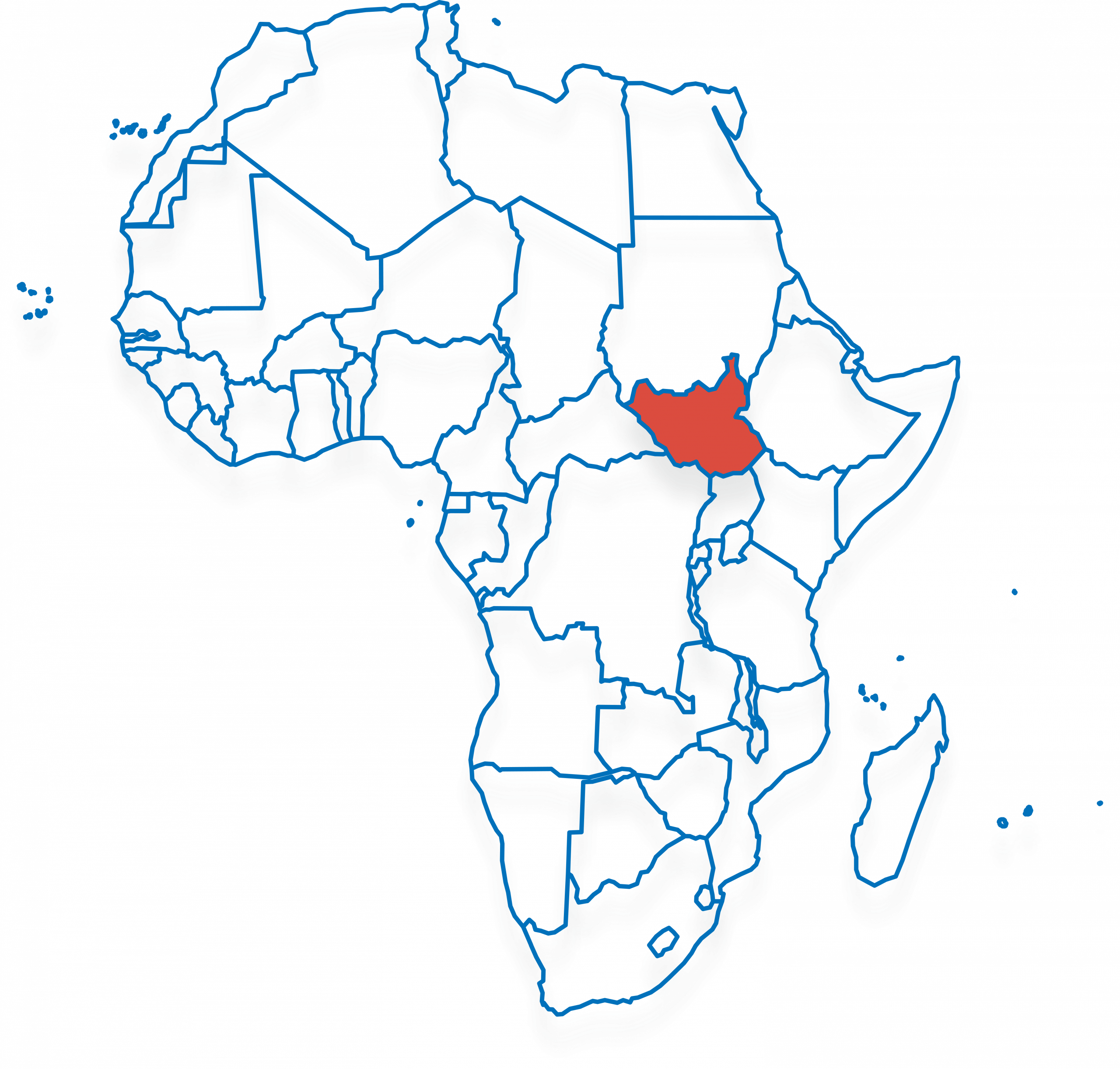

South Sudan

South Sudan is a landlocked country and shares borders with Sudan, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, Kenya, and Ethiopia.

The Agreement: In September 2025, Ambassador Apuk Ayuel Mayen, Spokesperson for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, stated that there is no formal agreement and “no discussions” with the United States on third country deportations. The Ambassador confirmed that there was “bilateral engagement” between the two countries on the May-July deportation of eight men.

South Sudan may be seeking reversal of U.S. policies targeting its nationals. On April 5, 2025, the U.S. Department of State (DOS) announced the revocation of all visas held by South Sudanese passport holders and banned their entry. On May 6, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) announced a 6-month extension of the designation for Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for South Sudan, a rare decision considering that all other TPS designations that have come up for review in 2025 have been terminated. (When the extended designation was due to expire on November 3, USCIS announced its termination, effective January 5, 2026.)

The People:

- May 20, 2025: 8 men from Cuba, Laos, Mexico, Myanmar, Vietnam, and South Sudan were put on a flight destined for South Sudan. Before completing the deportation operation, a federal court judge ordered the plane to reroute to a U.S. military base in Djibouti to afford the men opportunity for recourse. On July 5, 2025, the Administration completed the deportation operation, and the eight men were sent to South Sudan.

On May 20, 2025, the United States deported individuals protected by a federal court class action under D.V.D. v U.S. Dep’t Homeland Security to South Sudan with less than 24 hours’ notice. Attorneys representing the deported individuals filed for emergency relief on May 20. On May 21, a federal court judge ordered the federal government to maintain custody and control of the individuals. The judge also ordered that each individual must be given a chance to challenge their deportations to South Sudan and access to counsel. At a court hearing, the judge learned that class members were being held at a U.S. military base in Djibouti.

The individuals were detained in a converted shipping container by a nearby burn pit, which made it difficult to breathe. The individuals were also kept under 24-hour surveillance. As of June 23, at least one of the men represented by Human Rights First did not have a reasonable fear interview scheduled, the first step to challenging his deportation.

The U.S. federal government appealed the emergency relief to the Supreme Court. On June 23, the majority of the court issued a stay, clearing the way for the federal government to continue third country deportations for the individuals deported to South Sudan, as well as any other groups the federal government pursued for removal. On July 5, 2025, the eight men were removed to South Sudan.

On September 6, 2025, the Mexican man, Jesus Munoz-Gutierrez, was sent back to Mexico. The repatriation was brokered between South Sudan’s foreign ministry and the Mexican Embassy in Ethiopia, since Mexico currently has no embassies or consulates in South Sudan. South Sudanese officials said it received assurance from the Mexican government that he would not be subjected to torture, inhuman or degrading treatment, or undue prosecution. Munoz-Gutierrez told journalists that he “felt kidnapped” when he was deported to South Sudan.

Eswatini

Eswatini is a landlocked country, bordered by South Africa and Mozambique.

The Agreement: Human Rights Watch (HRW) reported that Eswatini agreed to accept 160 deportees for $5.1 million for the country’s border and migration management capacity. The agreement is valid for one year and can be renewed. Eswatini has agreed to accept individuals “with criminal backgrounds and/or who are designated suspected terrorists.

The People:

- July 16, 2025: 5 individuals from Vietnam, Laos, Yemen, Cuba (Roberto Mosquera del Peral), and Jamaica (Orville Etoria)

Eswatini’s spokesperson stated that all third country nationals would eventually be repatriated. All 5 individuals were initially kept at Matsapha Correctional Centre, a high security prison, in solitary confinement. The Eswatini Government said that the men would ultimately be sent back to their home countries but said there were no firm timelines for repatriation and did not clarify if the men would remain in prison. On September 21, one man from Jamaica was repatriated. In order to coordinate his repatriation, Eswatini sought support from the Jamaican Government and the International Organization for Migration (IOM). On October 6, the Eswatini government said that two others are expected to be repatriated soon.

Civil society groups protested the deportations outside the U.S. Embassy in Eswatini. The main opposition party released a statement criticizing the decision, calling it “human trafficking disguised as a deportation deal.”

On July 25, an Eswatini lawyer was denied access to the five men, even after filing official representation papers with the court. In August, he was finally granted access after launching a constitutional challenge on the denial of access to legal counsel. On September 2, the Legal Aid Society released a statement stating that they have been denied access to their client, Orville Etoria.

On October 28, 2025, Roberto Mosquera del Peral’s attorney said that he was on hunger strike for being kept in prison for more than three months. The Eswatini Government responded that he was currently “fasting and praying,” although close associates say this statement is false. Mosquera ended his hunger strike after 30 days.

- October 6, 2025: 10 individuals from Vietnam, Philippines, Cambodia, Chad, and Cuba

These individuals were also placed into detention facilities, and the Eswatini Government said that it would work with stakeholders for their ultimate repatriation.

A U.S. attorney representing three men from the October flight and two men from the July flight said that he has no way of getting in touch with his clients: “I cannot call them. I cannot email them. I cannot communicate through local counsel because the Eswatini government blocks all attorney access.”

In July 2024, Amnesty International expressed concerns about detention conditions at Matsapha Correctional Centre. An opposition politician who was jailed there was assaulted by prison guards and denied adequate food for four days. In the 2024 Human Rights Report, the U.S. State Department stated that there were “numerous credible reports” that security forces inflicted torture and other forms of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment to people in detention. According to the 2023 report, prison conditions were mixed throughout the country. Problems included poor ventilation, overcrowding, decaying of facilities, and prison violence.

The United States, and governments like Eswatini, risk violating international human rights laws by removing people to countries where they face a risk of serious harm or death. Four men who were deported earlier to Eswatini sued the Eswatini Government for due process violations, but their cases were delayed when an Eswatini High Court judge failed to appear for a scheduled court hearing without explanation.

The process to seek refugee status in Eswatini is under a significant backlog. Due to the backlog, refugees went without benefits or legal authorization to work for the extended waiting period. Once granted refugee status, “many waited more than a decade for citizenship without success.”

Rwanda

Rwanda is a landlocked country in East Africa and shares borders with Uganda, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Burundi, and Tanzania.

The United Kingdom Offshoring Agreement:

In April 2022, the UK Government, under Conservative leadership, announced the UK-Rwanda Asylum Partnership. Under the agreement, the UK would send people seeking asylum to Rwanda to have their asylum claims processed. In preparation, Rwanda built facilities that were fenced in, and it’s unclear whether asylum seekers would have had freedom of movement or opportunities to work. If asylum was granted, asylees could reenter the UK. If asylum was denied, individuals would be offered a chance to apply for asylum in Rwanda. Several countries have employed push-back strategies to offshore asylum, but the UK-Rwanda agreement was one of the first to propose sending asylum seekers who had entered UK soil to a third country on another continent to process their asylum cases.

Human rights advocates and international human rights organizations called the deal an erosion of refugee rights, and the UK Supreme Court ruled it unlawful under UK and international law because of the risk of refoulement. In July 2024, before any asylum seekers were ever sent to Rwanda, the newly elected Labour Government scrapped the partnership.

The UK-Rwanda Asylum Partnership would have cost UK taxpayers ₤1.8 million ($2.3 million) for every asylum seeker sent to Rwanda. And until the plan was abandoned, the UK paid Rwanda ₤290 million ($381 million), which Rwanda is refusing to pay back.

The U.S. Agreement: On June 3, 2025, an agreement was reportedly signed. The agreement states that the United States would provide an upfront payment to Rwanda of $7.5 million. The agreement was kept secret until August 5, when Rwanda announced that it reached an agreement with the United States to accept up to “250 migrants.” A spokesperson said that the United States sent a list of 10 individuals to be vetted by Rwanda. A spokesperson said that deportees would be provided with training, healthcare, and accommodation. Other implementation details are still being developed or not publicly known.

The agreement mentions Rwanda’s “established expertise” in managing returns, perhaps referring to Rwanda’s previous deal with the United Kingdom, which was ruled unlawful by the UK Supreme Court for risk of human rights violations.

The People:

- Mid-August 2025: 7 individuals of unknown nationalities

On August 28, the Rwandan government stated that 7 individuals arrived in mid-August. The spokesperson also shared that three individuals would return to their home countries and four expressed a wish to stay in Rwanda. The spokesperson said that those approved for resettlement in Rwanda would receive accommodation, workforce training, and health care. IOM and Rwandan social services have visited the individuals.

Ghana

Ghana is on the west coast of Africa and borders the Gulf of Guinea.

The Agreement: On September 11, 2025, President John Mahama said that the country had entered a deal with the United States and that 14 individuals had already arrived. Ghana said it would accept West African nationals, citing Ecowas’s free movement protocol that allows member state citizens to reside in other Ecowas countries visa-free for up to 90 days. Ghana said that no money was exchanged. Ghana would accept third country deportees and address the issue of its nationals overstaying their visas in the United States. Mahama implied that through this deal, Ghana had become the only country subject to visa restrictions to secure a complete reversal from the U.S. Administration.

The People:

- September 5, 2025: 14 individuals that includes nationals from Nigeria and the Gambia

Individuals were removed from the United States on a military cargo plane chained at the hands, waist, and ankles. At least two individuals were granted withholding of removal, meaning that the U.S. government promised that they would not be deported to their countries of origin. At least three individuals were granted deferral of removal under CAT, meaning that they were granted temporary protection due to the risk of torture if deported to their countries of origin.

According to court filings, individuals were informed that they would be removed from Ghana on September 12. Mahama stated that the Nigerian individuals were already returned to their country by bus. Facing imminent removal by Ghana, at least one individual was denied internet access, which was his primary way of communicating with his wife and lawyer. By September 15, all of the individuals had been sent to their home countries.

- Since September 2025, at least 42 individuals have been deported.

At least 8 individuals were dumped in Togo without documents. Some men were of other nationalities, including Nigeria and Liberia. A bisexual Gambian man said he was sent to Gambia where they criminalize same-sex relations. Ghana has allegedly conducted unlawful removals before, detaining and deporting Fulani refugees from Burkina Faso.

In November, a Sierra Leonean who was granted withholding of removal from the United States based on a fear of persecution or torture in Sierra Leone was deported to Ghana. Her wrists and ankles were shackled for the flight. In Ghana, she was kept in hotel for six days. When Ghanian officials tried to board her on a bus to Sierra Leone, she was dragged on the floor and sustained injuries

One of the deportees was detained at the airport for five days with no access to phones, showers, or change of clothes. At least eleven men were detained at Dema camp, a detention facility at a military training camp in a remote area outside of Accra. At Dema, the men were exposed to heat, mosquitos, and unsanitary water.

In October 2025, Ghanian lawyers filed a lawsuit challenging the agreement with the United States, arguing that it contradicts international treaties that Ghana has signed onto, including the Convention against Torture. Eleven individuals who were deported to Ghana also filed a lawsuit challenging their illegal detention at Dema camp.

Uganda

Uganda is a landlocked country in East Africa’s Great Lakes region and shares borders with South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Kenya.

The U.S. Agreement: On August 21, 2025, the Ugandan government announced that it signed an agreement with the United States. On September 3, a cooperation agreement, dated July 29, was made public. The Ugandan government prefers to accept nationals of African countries and will not accept individuals with criminal records or unaccompanied children. Uganda agreed not to send anyone to their home country until a final decision on their international protection claims has been reached. The agreement does not state if Uganda is receiving money or other diplomatic assurances. The Ugandan Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that the agreement is temporary and that details will have to be worked out.

- Currently, there are no known third country deportations to Uganda.

In November 2025, Uganda’s Minister of Relief, Disaster Preparedness, and Refugees announced that the government would not grant refugee status or protections to nationals from countries that are not at war, specifically naming Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Somalia. The minister blamed international aid cuts.

Uganda hosts the largest refugee population on the African continent. The country hosts about 1.8 million refugees and asylum seekers, mostly from South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Ongoing violence and protracted conflicts mean that new refugees arrive constantly. Uganda has long been heralded as a model refugee host country in the region, offering refugees access to land and public services. But due to constant refugee flows, Uganda’s inclusive policy is under threat due to increasing child protection gaps, humanitarian aid cuts, and donor fatigue.

The Netherlands Agreement: On September 25, 2025, the Netherlands and Uganda signed a Letter of Intent, or a promise to finalize an agreement that allows the Netherlands to use Uganda as a return hub. Individuals who have a final order of removal from the Netherlands and fail to leave voluntarily may be sent to Uganda. From there, individuals will be “expected to return to their country of origin.”

Equatorial Guinea

Equatorial Guinea’s mainland is south of Cameroon on the west coast of Africa and borders the Gulf of Guinea. Several islands are off the coast of the mainland, Bioko being the largest.

The Agreement: The Administration transferred $7.5 million to the Government of Equatorial Guinea from the Department of State’s “Migration and Refugee Assistance” account. In November 2025, Senator Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH) raised alarm about this highly unusual transfer and seeks information from Secretary of State Marco Rubio on whether this payment is for accepting third country deportations.

- On November 24, Human Rights First tracked an ICE flight to Equatorial Guinea that departed Alexandria, Louisiana, a known ICE deportation hub, on November 23. Human Rights First (HRF) confirmed that the flight carried third country nationals.

Countries in Asia

Bhutan

Bhutan is a landlocked country in the Himalayas, in between China and India.

The Agreement: There is no evidence of an agreement between the United States and Bhutan, Nepal, or India.

The People:

• March 25, 2025: 10 Bhutanese refugees deported via Delhi, India.

• April 7-14, 2025: 6 Bhutanese refugees

• In June, Asian Law Caucus stated that at least 27 Nepali-speaking Bhutanese refugees have been deported. Since February 2025, four U.S. removal flights have gone to Nepal and nine flights have gone to India.

Some individuals are stateless, since Bhutan will not recognize them as citizens and Nepal will not grant them citizenship. Due to Bhutan’s refusal to recognize the deported individuals as nationals, Bhutan is included in our third country deportations tracker.

At least four individuals had been resettled to the United States with refugee protections. One individual reported that he was given a choice between deportation to Nepal or Bhutan. He chose Bhutan, where he was held under strict surveillance, had his documents confiscated, and was forcibly smuggled into Nepal.

Individuals who have spoken to the media say that they were born in refugee camps in Nepal. They were deported to Bhutan, where their family faced persecution. Within 24 hours, they were expelled from Bhutan. Some are hiding in India or Nepal. At least four individuals have gone back to the refugee camps they were born or grew up in. Humanitarian aid groups have left the camps, and individuals have returned to destroyed huts.

In June 2025, the Nepali government issued deportation orders to four individuals and imposed fines. The government insisted that if they can’t return to the United States, they should go to Bhutan. On April 24, 2025, Nepal’s Supreme Court temporarily halted their deportations. The four men were allowed to return to the refugee camps they left as children while internal authorities investigated their cases.

At least one individual has died by suicide. Another individual is hiding in India where he has no ties or immigration status. Others have gone missing.

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan is in Central Asia, north of Afghanistan.

![]()

The Agreement: Uzbekistan agreed to accept its nationals. At least one deportation operation was funded by Uzbekistan.

The People:

• April 30, 2025: 131 individuals from Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) stated that the flight included individuals from Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. DHS also stated that the individuals were in the United States without authorization to stay. Uzbek media reported that Kyrgyz and Kazakh nationals will continue on to their home countries. Uzbek Foreign Ministry said in a Telegram post, “The repatriation process will be organized on the basis of humanitarian and legal principles, ensuring the dignified and safe return of citizens” (translated).

Responses

Federal Court Litigation

Since individuals are typically in some form of detention before being deported, immigration rights advocates and the press tracking ICE flights have sounded the alarm before potential flights. Individuals and public interest groups have launched federal court litigation to try to prevent unlawful deportations, enforce due process, and bring individuals back to the United States. Other litigation has sought to compel the federal government to release public information through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) lawsuits.

[More details upcoming.]

Non-U.S. Court Litigation

Once removed from U.S. soil and airspace, U.S. judges have limited power to stop the U.S. federal government and third countries from placing individuals into detention, subjecting them to mistreatment or torture, and deporting them to other countries, including a country where they may be persecuted or tortured. Human rights lawyers in third countries have launched litigation to try to release deportees from detention and prevent further human rights abuses.

Intergovernmental Organizations

- On May 13, 2025, the UN Human Rights High Commissioner voiced concern over U.S. third country deportations of Venezuelans and Salvadorans to El Salvador’s Centre for Terrorism Confinement (CECOT): “This situation raises serious concerns regarding a wide array of rights that are fundamental to both US and international law.”

- On July 8, 2025, UN Special Rapporteurs sounded alarm at the U.S. Supreme Court’s order clearing the way for the U.S. Government to resume third country deportations. They stressed that reasonable fear “assessments must be individual as well as country-specific.”

- On July 31, 2025, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights expressed concern for third country deportation agreements with South Sudan and Eswatini. The Commission called the deportations a “delegation of detention,” and raised concerns about violations to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and the African Guiding Principles on the Human Rights of All Migrants, Refugees and Asylum Seekers.

- On August 31, 2025, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights urged Rwanda and Uganda to ensure transparency of agreements and to ensure human rights. The Commission stated concern that the agreements may violate the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and that migrants are being sent to a “disposal zone” for arbitrary expulsions.

- On October 6, 2025, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees stated in a speech that he is worried about the legality of current deportation practices in the United States. He pleaded to countries, “When you decide to explore such arrangements, consult with us. Engage us.”

- IOM Policy on Return, Readmission, and Reintegration

Documents

- February 18, 2025 DHS Policy Directive on third country deportations

- March 30, 2025 DHS Memo, Guidance Regarding Third Country Removals

- July 10, 2025 ICE Memo, Third Country Removals Following the Supreme Court’s Order in Department of Homeland Security v. D.V.D., No. 24A1153 (U.S. June 23, 2025)

- September 24, 2025 Congressional Letter (Sen. Warren) seeking information on third country deportations

- November 10, 2025 Ranking Member Sen. Shaheen Letter to DOS Secretary Rubio asking for information about a $7.5 million transfer to Equatorial Guinea

More Trackers

- Human Rights First & Refugees International, Banished by Bargain: Third Country Deportation Watch

- Human Rights First, ICE Flight Monitor

- Council on Foreign Relations, What Are Third Country Deportations, and Why Is Trump Using Them?

Resources

- Justice in Motion (JiM) has created a post-deportation intake and referral form for U.S.-based advocates to request that JiM engage in post-deportation monitoring and response to detect potential rights violations that occurred during the arrest, detention and/or deportation. Upon receipt, JiM reviews and may task a member of the JiM Defender Network in MX, GT, ES, HN or NI, as appropriate (considering JiM resources + risk), to attempt communication with impacted or referenced deported migrants for a legal screening, and potential support connecting to local resources to meet immediate needs. JiM hopes to be able to help deported individuals connect or maintain connections to advice and legal representation, even after their deportation.

- January 29, 2025 NILA Practice Advisory, Protecting Noncitizens Granted Withholding of Removal or CAT Protection Against Deportation to Third Countries Where They Fear Persecution/Torture

- June 27, 2025 NILA Practice Alert, Third Country Deportations and D.V.D. v. DHS

- National Immigration Project, Fifteen Steps for Addressing Orders of Removal Issued by an Immigration Judge

Related Work by USCRI