Updates from the Front Lines:...

To commemorate National Human Trafficking Prevention Month, USCRI, along with the University of South Carolina, Georgetown University’s Institute for the...

READ FULL STORY

The açaí in your health bowl, the cocoa in your chocolate, the coffee in your latte, the copper in your phone—what do they have in common? Child labor. For millions of children, they represent long days of hazardous work instead of school, play, or rest.

On World Day Against Child Labor 2025, we pause to recognize an ongoing crisis that too often goes unseen: the exploitation of children within global supply chains. Nearly 138 million children—nearly 1 in 10 worldwide, and more than 1 in 5 in the world’s poorest countries—are engaged in child labor. Roughly half of them perform hazardous work that poses a threat to their health, safety, and future.

This year’s theme, Progress is clear, but there’s more to do: let’s speed up efforts, is a clear challenge to governments, corporations, and consumers: it’s time to move from awareness to accountability.

Supply Chain Issues

When corporate profits are prioritized and families are desperate to survive, children often pay the price. In communities where livelihood opportunities and access to education are limited, compounded by conflict and other destabilizing factors, children are frequently pushed into work to support themselves and their families.

Supply chains can exacerbate these vulnerabilities, particularly when there is little transparency or few legal consequences for corporate inaction. While many governments have committed to upholding international labor standards, enforcement remains inconsistent, especially in sectors that rely on informal, subcontracted, or rural labor.

Global supply chains are sprawling and complex, often involving multiple layers of suppliers across regions and countries. This complexity can obscure abusive labor practices, including child labor. Children are often exploited in smallholder farms, mines, textile workshops, and fishing communities, where oversight is weakest.

Some of the sectors where child labor is most prevalent include:

In November 2017, during the IV Global Conference on the Sustained Eradication of Child Labour in Buenos Aires, over 100 governments—including employers’ and workers’ representatives—pledged to eliminate all child labor by 2025. Building on the discussion from the conference, the International Labour Organization (ILO) released a report in 2018, outlining steps needed to end child labor by 2025.

Yet today, mid‑2025, the global situation remains deeply concerning. Progress has not only stalled but reversed in some areas. Between 2016 and 2020, the first increase in child labor in over two decades was recorded. Ratification and pledges alone have been insufficient.

This gap between ambition and reality makes it urgent to examine policy failures—and opportunities—that can restart progress and deliver on the commitments made in Buenos Aires.

Policy Gaps and Opportunities

Progress is possible—but only if political will matches the scale of the problem. Here are five urgent priorities for policymakers and advocates in 2025:

National governments and regional bodies must advance strong legislation that requires companies to identify, prevent, and remediate child labor across their global operations and supply chains. These laws should include:

Trade agreements and government procurement contracts should include binding labor rights clauses that penalize supply chains involving child labor. Countries can also expand import bans on goods made with forced or child labor.

While HREDD policies have been crucial in addressing child labor, voluntary corporate social responsibility is insufficient. Advocacy efforts must push multinational corporations to go beyond sustainability reports and trace their full supply chains, including informal and subcontracted tiers. Civil society should advocate for:

Full ratification of Convention 138 on the Minimum Age is needed to preserve children’s dignity, education, rights and safety. Convention 138 requires countries to establish a national minimum age for employment, which must not be lower than the age for completing compulsory education—typically 14 or 15, with exceptions permitted for lower-income countries. The convention is nearly universal and has been ratified by 177 countries. Only 10 countries, including the United States, have yet to ratify.

Ensure full implementation of Convention 182 on the Worst Forms of Child Labour, which mandates immediate action to eliminate the worst forms of child labor, including slavery, trafficking, forced labor, hazardous work, and child soldiering. Despite universal ratification, many countries have not fully implemented this convention.

Many countries lack adequate labor inspection systems, especially in rural or informal sectors where child labor is common. Some national laws are outdated or fail to define “worst forms” comprehensively. Others may exclude certain sectors, like domestic work or family farms. There is often also a lack of shelter, rehabilitation, or reintegration services for children removed from exploitation.

Universal ratification of Convention 182 shows a strong global consensus against child labor, but without meaningful, resourced implementation, many children remain in the very conditions the Convention seeks to eliminate.

While supply chain legislation and corporate accountability are essential, they are not sufficient on their own. To truly prevent child labor, these efforts must be paired with grassroots monitoring and area-based strategies that ensure children are not simply pushed into other harmful jobs. Such approaches center communities, civil society, and governments, not just corporations, in driving long-term solutions.

Child labor is not confined to specific supply chains. Children and families often shift between different types of work—agriculture, informal services, domestic labor—depending on economic need and local opportunity, not corporate boundaries. This means interventions targeting a single supply chain can be easily bypassed. For example, a child removed from a cocoa plantation due to supply chain audits may end up in illegal mining or informal street vending, often in equally hazardous conditions.

Area-based strategies address these dynamics by focusing on root causes. Investing in local services, community-level monitoring, and family livelihoods can reduce the push factors of all forms of child labor. Child labor thrives where safety nets fail. Prevention requires greater investment in education, food security, and social protection—especially for migrant and refugee families, survivors of trafficking, and other displaced populations.

Many child laborers work in small, informal operations, such as family farms or street trades, that fall entirely outside formal supply chains. These settings demand community-driven responses. Local unions, child rights groups, and grassroots organizations are often the first to identify exploitative practices. To be effective, they need sustained funding, legal protection, and recognition as frontline defenders of children’s rights.

A Call to Action

On this World Day Against Child Labor, we must center children’s rights in every conversation about trade, labor, and the global economy. As advocates, we can push for:

Ending child labor in supply chains is not only possible—it is essential for building a just and equitable global economy. The invisible hands that build our world deserve protection, education, and dignity, not exploitation.

#WorldDayAgainstChildLabor #EndChildLabor #SupplyChainJustice #PolicyForChildren

[1] HREDD – refers to internal processes that companies, including financial institutions, use to identify, prevent, and reduce negative environmental and human rights impacts. It requires a systematic and thorough investigation or review of facts to reduce risk.

To commemorate National Human Trafficking Prevention Month, USCRI, along with the University of South Carolina, Georgetown University’s Institute for the...

READ FULL STORY

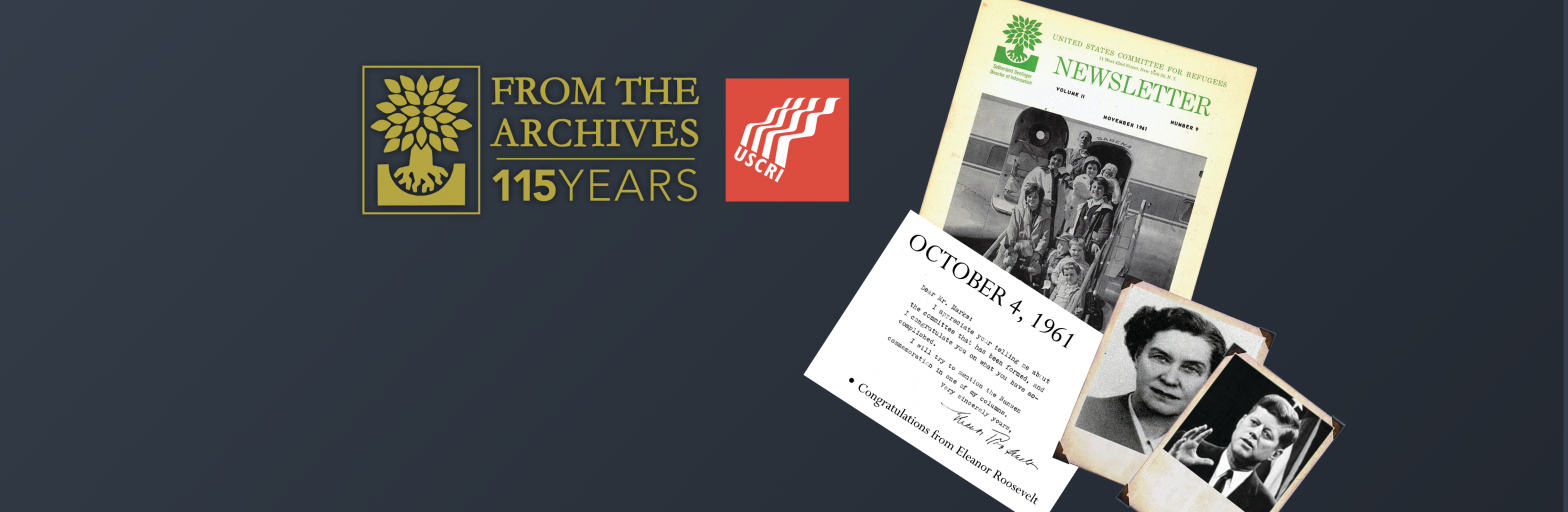

For more than a century, the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants has advocated for the rights and dignity of refugees,...

READ FULL STORY

By Veronica Farkas, TVAP/Aspire Case Manager My job as a Case Manager is a combination of advocacy, crisis response, and long-term...

READ FULL STORY