TURNING PERIOD POVERTY FROM STRUGGLE...

By Firdaus Bashee - Country Director, USCRI Kenya and, Sudi Omar Noor Founder, Girl Power Action Initiative (GPAI) In...

READ FULL STORY

Earlier this year, humanitarian parole protections for individuals covered by the Cuban, Haitian, Nicaraguan, and Venezuelan (CHNV) parole program were categorically revoked, placing more than 500,000 people at risk of deportation. More than 100,000 Cubans were covered by the program.

Driven by Cold War politics, the United States has long pledged itself as an ally of the Cuban people’s plight for freedom. In the aftermath of the Revolution in 1959, Cubans found it relatively easy to gain admission to the United States. Now, the termination of CHNV undermines this legacy of welcome.

What is CHNV?

Humanitarian parole, as provided in the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), allows the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to permit the entry and residence of select individuals for “urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit.” Parole has been used as a tool to respond to humanitarian crises numerous times over the past several decades, particularly in response to unsuccessful American wars . In the aftermath of the fall of Saigon, the United States welcomed over 100,000 of our Vietnamese allies and their families on humanitarian parole. Nearly 50 years later, parole was once again used as a tool to rapidly evacuate our Afghan allies and bring them to the United States.

CHNV parole allowed nationals of Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela to come to the United States and work with the support of a sponsor. One of the primary goals of the CHNV program was to reduce irregular border crossings. By this measure, the program was a resounding success, with arrests of CHNV nationals dropping by 90%. The program’s en masse revocation thrust its recipients into uncertainty.

Litigators quickly filed for relief, challenging the Administration’s decision to revoke parole for CHNV recipients. In April, Judge Talwani in Massachusetts stayed DHS’ move to terminate benefits for existing parolees covered by the class action. A May decision by the Supreme Court blocked Judge Talwani’s order, allowing DHS to proceed with revoking the residency and work authorizations of CHNV parolees. The lawsuit remains ongoing.

Cubans admitted to the United States on CHNV humanitarian parole are now being threatened with return to Cuba. Arguably, compared to Venezuelans, Haitians, and Nicaraguans, Cubans are in an advantageous position—those who have resided in the United States for one year are able to apply for a Green Card under the Cuban Adjustment Act (CAA). But even adjustment under the CAA is now under crackdown, with Green Card applications associated with the Act on hold.

USCRI, founded in 1911, is a non-governmental, not-for-profit international organization committed to working on behalf of refugees and immigrants and their transition to a dignified life.

For inquiries, please contact: [email protected]

By Firdaus Bashee - Country Director, USCRI Kenya and, Sudi Omar Noor Founder, Girl Power Action Initiative (GPAI) In...

READ FULL STORY

By: Alexia Gardner, USCRI Policy Analyst, and Anum Merchant, USCRI Policy Intern Extreme weather continues to drive new large-scale displacement, with 2024 ranked among the highest years...

READ FULL STORY

As part of the Intercultural Mobility Week held in October 2025, the Welcoming Communities Program at USCRI Mexico, through the...

READ FULL STORY

Katharine I. Crost brings to the organization wide-ranging experience in the field of securities and corporate finance as well as non-profit leadership.

Ms. Crost was a partner at Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe, LLP for over 30 years. Her extensive portfolio at Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP included serving on the Firm’s Executive Committee, establishing and chairing the firm’s Women’s Initiative and acting as a Practice Group Leader.

Ms. Crost has been a passionate advocate on behalf of immigrants, refugees and global citizens worldwide. She has served as a Board Member of the Women’s Refugee Commission and currently serves as a Member of the Emeritus Board of Indego Africa, a non-profit that works to provide artisan women and young people in Africa training for sustainable livelihoods and access to markets. Her commitment to empowerment and social justice has taken her to refugee camps in Ethiopia and Myanmar. She has represented pro bono clients in researching and preparing a report on shelters for unaccompanied minors and a training protocol for border patrol agents to screen for human trafficking victims. She currently volunteers at USCRI’s field office in Albany, New York.

Katharine Crost earned a J.D. from the University of Virginia School of Law and a Bachelor of Music degree from Michigan State University.

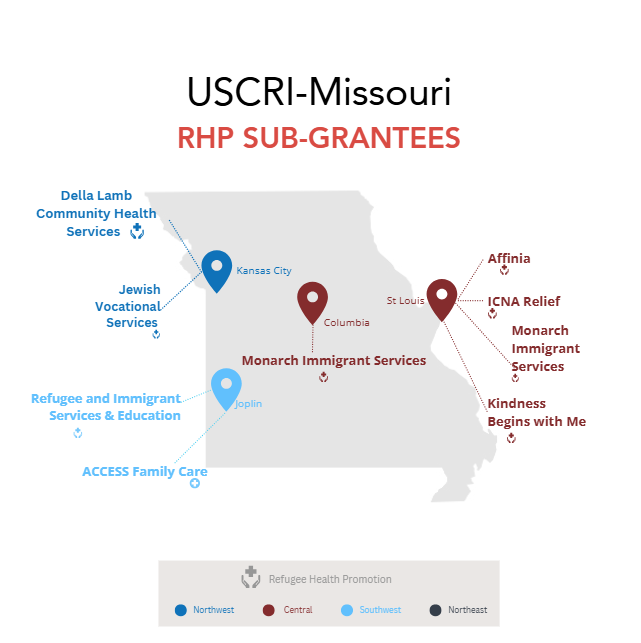

Refugee Health Promotion (RHP) is a Refugee Support Services (RSS) set-aside program that promotes the health and wellbeing of refugees and other ORR-eligible groups for up to 5-years from date of arrival to the U.S. or date of ORR-eligibility by:

1) Providing opportunities to increase health literacy,

2) Coordinating physical and mental health care; and

3) Organizing wellness group activities.

RHP-funded organizations may provide services that fall under one or more of these categories, which is dependent on each individual agency’s annual proposal and program design. The nature of services provided can also vary by agency, even within the same category, so it is always best to reach out to them directly to obtain information and coordinate care.

Health Education Program (HEP):

Health Education Classes and Targeted Health Outreach to Individuals. Programs provide opportunities to increase health literacy for eligible populations, empowering clients to make informed health decisions.

Health Navigation Program (HNP):

Medical and Mental Health Navigation and Support. Programs coordinating health care for individuals and providing services to ensure individuals can navigate and access complex health care systems.

Wellness Program (WP):

Adjustment Groups, Skill-Building Networks, and Peer Support Meetings. Programs organize wellness groups to connect individuals with social groups and learning activities that promote their health and well-being.

Missouri Refugee Health Services subcontracts with a combination of community-based organizations, federally qualified health centers and local resettlement agencies to implement the above programs.

Saint Louis:

Joplin

Columbia

Kansas

USCRI administers this program to provide high quality, cost-effective health benefits to refugees and other ORR-eligible groups, who are ineligible for Medicaid in Missouri.

RMA provides up to 4 months of health insurance that mirrors the state’s Medicaid program for adults without children or others in special circumstances, such as adults 65+ or living with a disability who are pending SSI/Medicaid.

In Fiscal Year 2027, with H.R.1 (“OBBA”) ending decades of Medicaid coverage for refugees and other humanitarian parolees, Missouri’s RMA usage is expected to grow exponentially for newcomers. This program, however, will continue to only cover refugees for up to 4-months from their date of arrival to the United States, even with upcoming shifts in policy leaving many refugees uninsured for long periods of time until their status is adjusted to meet Medicaid program eligibility.

In response to the H.R.1, USCRI is creating a directory for low-cost and free healthcare providers in Missouri. To accomplish this goal, USCRI has created a form to gather health resources that currently exist in the major Missouri regions of resettlement. If you are aware of a free or an affordable healthcare service in your community, please take a few minutes to fill out the form, by clicking here or using the QR code.

MO RHS partners with local agencies in Saint Louis, Kansas City, Columbia, Joplin and Springfield to enroll eligible clients into the RMA program.

Saint Louis:

Kansas City:

Joplin:

Columbia:

Springfield:

USCRI Missouri maintains a Resource Hub and a Master List of Resources which are consistently updated.

Looking for potential partnership opportunities, or in need of support or additional resources please reach out to us at [email protected].

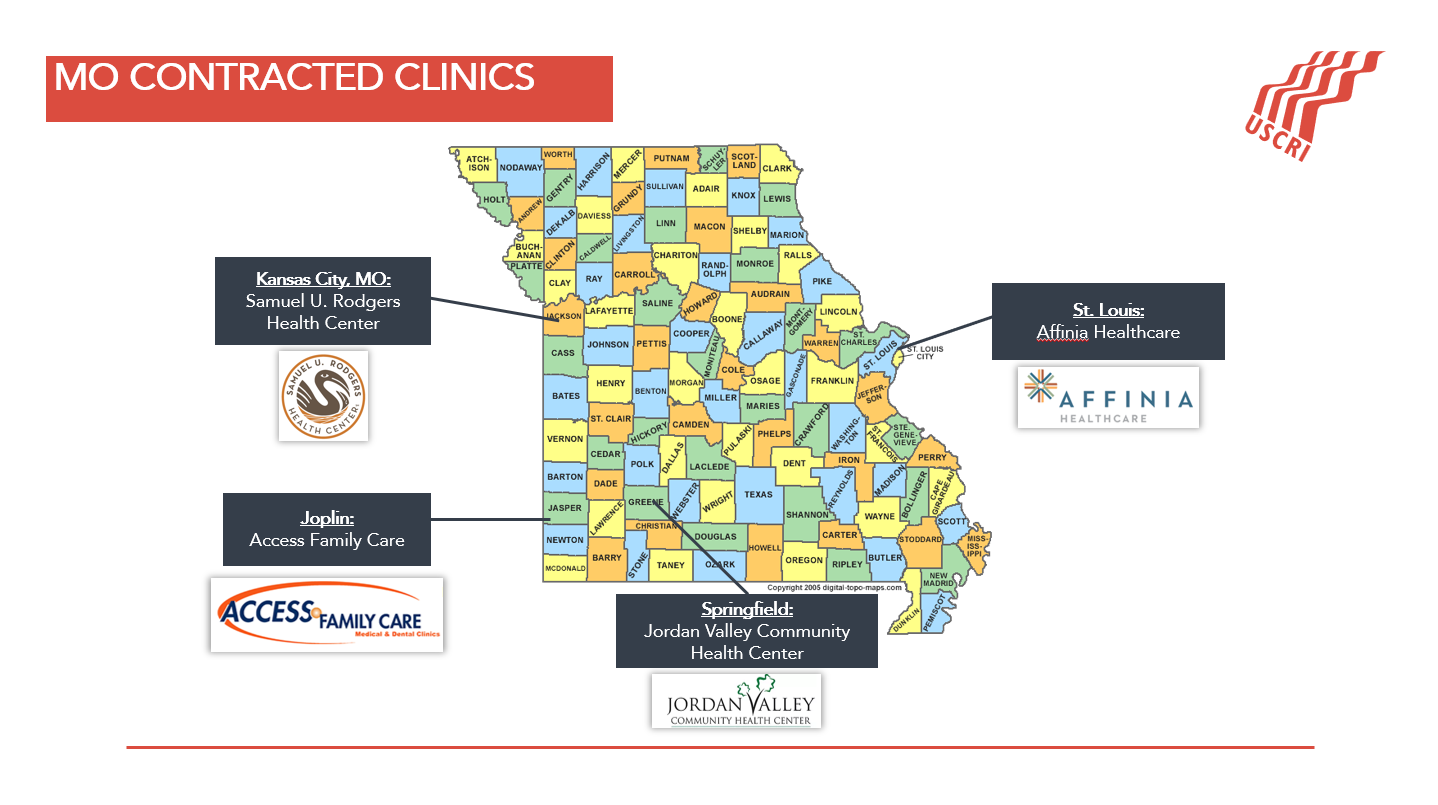

USCRI administers this program to provide domestic refugee physical and mental health assessment, identify communicable diseases of potential public health importance and referrals to primary healthcare providers.

The Refugee Medical Screening program conducts the domestic health assessment for new ORR-eligible arrivals, following guidance issued by ORR and Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC), referring clients to primary care and specialists as needed.

The Refugee Medical Screening must be completed for each new ORR-eligible arrival within 30-90 days post arrival to the United States or from their date of ORR-eligibility.

Missouri Refugee Health Services subcontracts with four federally qualified health centers to provide complete domestic health assessment and vaccinations to new arrivals. Those clinics are located in Saint Louis, Kansas City, Joplin and Springfield:

It is important to note that immunizations given at or during Refugee Health Screening appointments are the same ones required for the Adjustment of Status (or “Green Card”) process with a Civil Surgeon. Initiating Medical Screening as soon as ORR-eligible individuals meet eligibility is very important and ensures that families are more prepared for Status Adjustment when they file for their I-693 application.

Through training opportunities and resource sharing, the Refugee Wellness Program (RWP) empowers local organizations and community members to feel confident supporting refugees building resilience and encouraging them to seek help for physical and mental health challenges.

Trainings Options: All program trainings are free, two hours in length and are offered virtually or in-person.

Intersection of Culture and Trauma in the Care of Diverse Population: Training helps participants understand how to provide culturally informed and trauma informed care, as well understand the nuances of mental health cross-culturally.

Intersection of Culture and Trauma in the Care of Diverse Populations: Refugee and Immigrant Youth Training helps participants understand culture, trauma and mental health as it relates to refugee and immigrant youth in the classroom.

DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT

Christine Herrmann became USCRI’s Director of Development in the summer of 2025, taking on the role as the organization faced widespread federal funding rescissions. The position allows her to lead a dedicated team of fundraisers while staying emotionally connected to her immigrant ancestors. Replacing government funding with new sources of support may seem like an immense job, but people are being incredibly generous in helping immigrants and refugees who want to be New Americans and live better lives.

Christine has worked in the nonprofit world for 20+ years at organizations like Physicians for Social Responsibility, National Academies of the Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, the Red Cross and National Association for the Education of Young Children. Her work has focused on development, strategic growth, board/staff engagement and advocacy. Throughout her career, she has been inspired by colleagues striving for a better world and has connected with donors who share that passion and purpose. Some have dedicated their lives to confronting climate change and ending the threat of nuclear weapons. Others dream of a world where everyone has food, shelter, and the chance of a great education beginning before birth. All of them share a belief in seeing goodness beyond color or ethnicity.

She has served as president of the Friends of SW DC Public Library, as a board member of Maine Writers & Publishers Alliance, and as a mentor to middle school girls through Higher Achievement.

Christine received her BA in International Relations from San Francisco State University. She is a writer and artist in her spare time.

DIRECTOR OF REFUGEE SERVICES

Zeze Rwasama is Director of Refugee Services. He has dedicated the 20 years of his life providing social integration and self-sufficient services to refugees and immigrants. Prior to joining USCRI, I was the Executive Director of a local refugee resettlement for 10 years and currently overseeing the implementation of the Initial Resettlement, Matching Grant and Preferred Community programs at USCRI focusing on program outcomes, technical assistance, monitoring to ensure quality of services and compliance of federal guidelines.

Zeze’s childhood dream of pursuing a career in electronics engineering took a turn towards helping disadvantaged refugees when he became a refugee. His personal journey as a refugee in 1995 ignited his passion for supporting refugees, leading him to accumulate extensive refugee services experience both within and outside the United States.

Additionally, he has contributed his expertise to the boards of several non-profit organizations, including the Unity Alliance of Southern Idaho, Culture for Change, and the Valley House Homeless Shelter

DIRECTOR OF POLICY AND COMMUNICATIONS

SENIOR DIRECTOR OF FIELD OFFICES AND LEGAL SERVICES

FINANCE COMMITTEE CHAIR

Gene DeFelice is an accomplished attorney as well as a seasoned corporate executive. His areas of expertise include business management, compliance and corporate governance.

Mr. DeFelice is currently the Managing Director of Novo Strategic Partners, a company specializing in legal and corporate management solutions including compliance; governance; human capital; licensing, mergers and acquisitions; regulatory issues; legislative affairs; and forensic services. Previously Mr. DeFelice served as the Senior Vice President and General Counsel for Rackspace, a global leader in cloud computing and IT infrastructure with approximately 6,200 employees and $2 billion in revenue. He was Executive Vice President, Corporate Counsel and Corporate Secretary for HMS, a $450 million public healthcare technology, healthcare data analytics and medical services company. He has extensive experience in management, compliance and governance in Fortune 500 companies across a number of industries, including medical technology, healthcare analytics, pharmaceuticals, cloud computing and IT infrastructure.

Mr. DeFelice has sat on the boards of a number of non-profit organizations, donating his time and expertise to improving non-profit management and operations. He served for many years as USCRI’s Board Chairman.

Mr. DeFelice graduated from Rutgers University, earned an M.B.A. with distinction from Webster University in Switzerland, and was awarded a Doctor of Law from Seton Hall University.

Gabriel Lajeunesse is a financial advisor and former U.S. Air Force officer with over 30 years of experience in national security, wealth management, and community development.

He served for two decades in international security roles, including assignments advising the Joint Chiefs of Staff and supporting National Security Council committees at The White House. His final deployment to Afghanistan included leading a multinational team of over 600 personnel. He is a Bronze Star recipient for his service in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Following his military career, Mr. Lajeunesse transitioned into financial advising, specializing in portfolio strategy, business transitions, and real estate investments. He holds certifications as a Certified Exit Planning Advisor and Accredited Asset Management Specialist, and is admitted to the D.C. Bar.

He is the founder of Aacred Development Holdings, a real estate private equity firm focused on Smart Growth housing in Northern New England. He also serves as a planning commissioner and member of the Vermont Community Development Board.

Mr. Lajeunesse holds degrees from the University of Massachusetts Lowell, Naval Postgraduate School, Georgetown University Law Center, and an Executive MBA from the Quantic School of Business and Technology.

John T. Monahan, JD, is interim dean at the School of Nursing & Health Studies and senior advisor to Georgetown University’s President. A Georgetown community member for many years, he holds Georgetown academic appointments as Professor of Medicine, Senior Lecturer at Georgetown Law, and Senior Fellow at the School of Public Policy, and has taught courses at NHS, Georgetown Law, and the School of Foreign Service.

Over the course of his professional career, the core of Monahan’s work has focused on addressing complex health and social service programs affecting vulnerable populations in the United States and internationally.

In his varied career, Monahan has served as Legal Counsel to US Senator David Pryor; Law Clerk to US District Court Chief Judge John Grady; and is a veteran of numerous political races, including the Mondale and Clinton presidential campaigns. A member of the Council on Foreign Relations, he serves on the boards of the National Network for Public Health Law, US Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, and Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless.

Monahan holds bachelors and law degrees cum laude from Georgetown University.

VICE CHAIR & DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE CHAIR

Jeffrey Metzger, an attorney who has worked in corporate, government, and private practice, brings to USCRI’s Board of Directors extensive legal expertise in ethics and compliance as well as a personal drive to serve the refugee and immigrant community.

Most recently, Mr. Metzger was Staff Vice President and Associate General Counsel of Unisys Corporation, where he was responsible for the company’s litigation, counseling the company’s government businesses, and directing the company’s federal government contracts organization. He also designed the company’s first ethics compliance program and then served as Corporate Ethics Officer.

Before coming to Unisys, Mr. Metzger served on the professional staff of the President’s Blue-Ribbon Commission on Defense Management, where he was principally responsible for making recommendations on defense industry compliance issues. He also served in the Civil Division of the Department of Justice for a number of years, representing the United States in procurement fraud and government contract litigation. Before joining Justice, he worked in private law practice in Washington, D.C.

He earned a B.A., magna cum laude, from Amherst College, and a J.D. from Georgetown University Law School.

Bart Bachman is the Associate Director of Trafficking Services at the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants (USCRI), where he oversees administration of the Trafficking Victim Assistance Program (TVAP) and the Child Trafficking Victim Assistance Demonstration Program (Aspire). He started with USCRI’s TVAP program in 2017 and previously served as the regional Program Officer monitoring project implementation in ACF Regions 1, 2, 3, and 10. Prior to joining USCRI, Bart worked at the Migration Policy Institute in its International Program, where he published an article in the Migration Information Source entitled “Diminishing Solidarity: Polish Attitudes toward the European Migration and Refugee Crisis.” He holds an M.A. in German and European Studies and a B.S. in International Politics from Georgetown University.

DIRECTOR OF INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMS

Taylor McNaboe is the Director of International Programs at the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants (USCRI). In his role, he oversees USCRI’s international programs in El Salvador, Kenya, Mexico, and Honduras in addition to undertaking the expansion of USCRI’s field offices in Latin America and Africa. He began working at USCRI in 2021 as a Program Assistant for the Reception and Placement (R&P) and Afghan Placement and Assistance (APA) Programs. Additionally, Taylor has prior experience with NGOs in the Middle East and North Africa that deal with migration-related issues. He has an MA in Intercultural Mediation in the Mediterranean Region from Cà Foscari University and an undergraduate degree in French and Chinese from the University of Edinburgh.

DIRECTOR OF EL RINCONCITO DEL SOL SHELTER

With over 25 years of dedicated experience in working with vulnerable youth, Alejita Rodriguez brings a wealth of experience to the field of social work. In 2021, Alejita joined USCRI as the shelter Director of Rinconcito del Sol, a role that highlights her unwavering commitment to improving the lives of children. Alejita earned her Master’s degree from Grand Valley State University where she developed a solid foundation of knowledge and skills to address the complex challenges faced by vulnerable youth. Throughout her career, she has demonstrated a profound commitment to program development, ensuring programs are both innovative and effective. This dedication extends to compliance, as she is well-versed in regulatory and legal requirements, ensuring the utmost safety and quality of care for the children under her supervision. Alejita has been a catalyst for youth development, using her experience to create supportive, nurturing environments that enable children to thrive.

DIRECTOR OF REFUGEE HEALTH SERVICES

Dr. Gursimran Grewal is a trained Medical Doctor with a wealth of experience in global public health, specializing in Sexual and Reproductive Health, Family Planning, Maternal and Child Health, and HIV/AIDS. Over the past decade, she has provided technical leadership, project management, and financial oversight for large-scale programs across Asia and Africa, in partnership with international NGOs, private sector organizations, and governmental bodies. Her programs have been funded by a range of major donors, including BMGF, USAID, CDC, and others.

Currently, Dr. Grewal serves as the Director of USCRI’s Refugee Health Services, where she focuses on promoting the health and well-being of refugees resettled in the United States. She oversees the development and implementation of culturally sensitive and linguistically appropriate health assessments, education, and referrals, working collaboratively with community partners to ensure high-quality care and support for refugees.

VICE PRESIDENT OF STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT

Mike is a non-profit leader and fundraising professional who has worked with refugee and international development organizations for more than 20 years. As Vice President of Strategic Development his team raises support for USCRI’s critical programs from the US government, foundations, corporations, and individual Americans. Prior to USCRI, Mike served as the Executive Director of Ripple Effect US, a charity raising awareness and support in the United States for smallholder farming families in East Africa. He also served as Director of Development at Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service and spent eight years at the US Association for UNHCR—the UN Refugee Agency—in various roles, including Associate Director and Acting Executive Director. Mike has a MA in International Peace and Conflict Resolution and a BA in International Studies from American University. When he is not performing in his professional capacity, he is performing the duties of a husband and avid sports fanatic, rooting enthusiastically for his favorite football and college basketball teams.

TREASURER

Katharine Laud’s path has combined finance and non-profit management to provide opportunities to under-served communities, including women, minorities, immigrants and people of color for wealth creation.

Ms. Laud is currently the President of Opportunities Credit Union, the 11th largest credit union in Vermont, which offers innovative and affordable financial services to Vermonters. Before assuming her current position, Ms. Laud was the Associate Vice President for Finance and Administration at the University of Vermont Foundation, a non-profit organization committed to serving the university community. She was the Chief Financial Officer of a non-profit that focused on affordable housing for low-income people. Ms. Laud has served on a number of corporate boards, including the Board of Directors for Provident Financial Services, a NYSE-trading bank holding company, a member of the Audit and Governance Committees and as Chair of the Wealth Management Committee. While serving on the Board of Directors of the First Morris Bank and Trust. She was instrumental in the founding of the Wealth Management Division.

Ms. Laud has used her extensive background in finance to build avenues to wealth creation and management for diverse and under-served communities in Vermont. She has brought corporate efficiencies to non-profit management to promote economic self-sufficiency among low-income people.

Katharine Laud earned a B.A. and an M.B.A. at Dartmouth College.

CHAIR

Earl Johnson serves as a Member of USCRI’s Board of Directors following a decades long career in public service at the federal and state level. Mr. Johnson has been a leader nationwide in promoting responsible fatherhood and economic security issues related to men and boys of color.

He was appointed by the White House to serve as the Director of the Office of Family Assistance (OFA) with the Department of Health and Human Services’ Administration for Children and Families (HHS/ACF). In this position Mr. Johnson oversaw an annual budget of $17.8 billion. In this role, he was the principle policy and administrative manager for the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program.

Before accepting his current position, he was the Senior Policy Advisor and Interim Workforce Investment Board Director for the City of Oakland and Mayor Ron Dellums. Prior to that he was the Senior Program Officer for the California Endowment and the Associate Director for the Rockefeller Foundation’s Working Communities Division. He also served as the Associate Secretary for Planning and Evaluation for the California Health and Human Services Agency.

Mr. Johnson has worked serving families and children for his entire career. He brings this passion to USCRI’s programs for refugee and migrant families and children.

Earl Johnson has a Ph.D. from UCLA’s School of Social Work and Public Policy. He holds an M.A. from the University of Chicago, Harris School of Public Policy and a B.A. in Political Science from the American University in Washington, D.C. He has also completed Harvard University’s Executive Management Program on Negotiation.

PAST CHAIR

Diann Dawson’s more than 38 years of distinguished public service as a senior executive combined with her leadership in the private sector adds immeasurable value to the work of USCRI’s Board of Directors.

Ms. Dawson is currently President and CEO of DDA & Associates, a human services consulting firm. She is a national and global advocate for children and family strengthening initiatives and serves as a director on several non-profit boards.

Prior to her retirement as a senior executive, she served as the Director of the Office of Regional Operations within the Administration for Children (ACF) and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. As principal advisor to the Assistant Secretary on field operations, she provided executive leadership and directions to ACF’s ten regional offices on the integration and coordination of more than 65 human services programs to promote the well-being of children, families and communities.

Ms. Dawson’s extensive experience working at the senior leadership level for ACF led her to become a passionate advocate for children and family issues worldwide. She brings hands-on experience in operations and directions to USCRI’s work, helping the organization run model programs to serve refugee and migrant children and families.

Ms. Dawson earned a B.A. from Bennett College, an M.S.W. from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and a J.D. from the Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law and is admitted to the D.C. and Maryland bars.

PROGRAM DIRECTOR AT RAYO DE LUZ

Annahi Ruano has over a decade of experience working in human services and the criminal justice system. In 2013, she became a Behavioral Health Therapist specializing in family therapy and individual therapy for children 5-17 in the foster care system. She began working at ORR shelters in 2017 as a Clinician in Arizona in a 400-bed shelter for Southwest Key Casa Kokopelli and transitioned to Lead Clinician/PSA Compliance Manager in California for Casa San Diego a 90-bed shelter with three locations/ licensees for boys and girls 5-17. She later became the Program Director/CA Program Administrator with Southwest Key Programs for Casa San Diego. She has a passion is helping children and families in need and her heart is with immigrants, as she comes from immigrant grandparents and parents who came to the United States for a better future for future generations. She holds a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice and a master’s degree in forensic psychology.

VICE PRESIDENT OF REFUGEE PROGRAMS

Dylanna Grasinger is the Senior Director of Field Offices for the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants. Ms. Grasinger has over 20 years of experience in helping protect the rights of refugees and immigrants in local communities. Prior to taking on her current role, Ms. Grasinger served as the Director of USCRI Erie. She has also served in various leadership positions throughout the Midwest, United States as well as Bursa, Turkey. She has extensive experience in program development, budget oversight, compliance, and transformational leadership. She holds a B.A. in English from Kent State University, where she also received certification in Teaching English as a Second Language. She also earned an M.S. in Negotiation and Conflict Resolution from Creighton University.

ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS

Kelci Sleeper is the Associate Director of Communications at USCRI, where she oversees the Communications team and all USCRI communication, including social media, website design and maintenance, public relations, email marketing, branding, graphic design, and more. Most recently, she led the Marketing and Communications team for Big Brothers Big Sisters in Atlanta. Kelci has an MA in Public Relations from the University of Georgia and a BS in Journalism and Mass Communications from West Virginia University.

DIRECTOR OF MANAGEMENT INFORMATION SYSTEMS

Wony plans, coordinates, directs, and designs all operational activities of the MIS department, as well as provides high availability and security solutions that enhance mission-critical business operations and continuity. He has over 22 years of information technology experience in both the private and nonprofit sectors. Prior to joining USCRI, Mr. Pak worked as a Network Engineer and System Integrator at various companies including Technology Automation Management Inc., Comstor Inc., and RHI. He completed Local Area Network study at Computer Learning Center and has achieved various IT training and certifications including CNE, MCSE, and CCSA. Mr. Pak holds B.A. in Music Composition at the University of New Orleans.

VICE PRESIDENT OF CHILDREN'S SERVICES

Matt is responsible for the oversight of USCRI’s Children’s Services including the Home Study and Post Release Services for Unaccompanied Children, READY4Life, and the Unaccompanied Children Resource Center. Matt is a clinical social worker who has been working with refugee and immigrant youth for more than 15 years. He previously worked as therapist with immigrant youth and oversaw housing programs for runaway and homeless youth at the Latin American Youth Center. He later managed the Unaccompanied Refugee Minor program in Washington, DC at Lutheran Social Services of the National Capital Area. Matt served as a Peace Corps volunteer in the Dominican Republic and received his Masters of Social Work from Columbia University. He has been working at USCRI since 2016.

Eskinder Negash is President and CEO of the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants (USCRI), an organization founded in 1911 to protect the rights and address the needs of persons in forced or voluntary migration worldwide and support their transition to a dignified life. Mr. Negash is a recognized senior executive leader and brings nearly 40 years of proven non-profit management experience on behalf of refugees and immigrants.

Prior to joining USCRI, he served from 2009-2015 as Director of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), the largest government-funded refugee resettlement organization in the world. With a budget of over $1.5 billion, the ORR plays a critical role in providing essential services to a wide range of vulnerable people through the Resettlement Program, Rescue & Restore anti-trafficking campaign, and the Unaccompanied Children’s Program. Under his leadership, ORR served more than 850,000 people in six years.

Under Negash’s leadership, ORR served more than 400,000 refugees, 150,000 asylees, 125,000 Cuban and Haitian Entrants, nearly 21,000 Iraqi and Afghan Special Immigrant Visa holders, 3,200 Victims of Trafficking, over 32,000 U.S. repatriates, and almost 116,000 unaccompanied children, totaling more than 850,000 people during his six years of service.

Prior to his appointment by the Obama Administration, Mr. Negash served as the Vice President and Chief Operating Officer of USCRI for seven years. He also was the Vice President and Chief Administrative Officer of the International Institute of Los Angeles for 15 years. Mr. Negash served as a board member with several non-profit organizations, including two years as Chair of the Joint Voluntary Agencies Committee of California, Chair of the California State Refugee Advisory Council, and Board Member of the Coalition for Human Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles (CHIRLA).

In 2016, Mr. Negash served in the Secretary of State’s Advisory Committee for Public-Private Partnership considering the formulation of U.S. polices, proposals, and strategies for developing public-private partnership that promote shares value with the private sector worldwide. In 2009, Mr. Negash received an “Outstanding American By Choice” award from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services in the Department of Homeland Security, which recognizes naturalized U.S. citizens who have made significant contributions to both their community and their adopted country. In 2010, the International Rescue Committee (IRC) honored Mr. Negash as one of ten distinguished men and women whose stories of hope and transformation epitomize the refugee journey.

CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER

Xavier Graham joined USCRI in 2019 as the Director of Finance and Compliance. Prior to joining USCRI, Mr. Graham served as the Executive Director of Finance with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children leading the finance operations. He also served in several leadership positions in New York City and London. He has over 15 years of accounting and finance experience working with private, non-profits and public practice. Mr. Graham is a Certified Accountant and holds a Master’s degree in Accounting & Finance studies.

Jeff Kelley has spent his career both in public service and in the private sector, focusing on communications, public affairs and government relations. He has worked for both the U. S. government and the private sector in the U.S. and Europe.

Most recently, Mr. Kelley served in the Obama Administration as Director of Public Affairs for the Administration for Children and Families. ACF houses programs such as refugee resettlement (ORR), Head Start, child welfare and foster care, and the nation’s family assistance program (TANF).

Mr. Kelley owned Peer Communications LLC, where he organized conferences on communications strategy for the senior public affairs executives of more than 100 Fortune 500 companies. He worked for more than 20 years for the DuPont Company, first as executive speechwriter for the Chairman, then in several senior management roles, including more than a decade in Geneva, Switzerland, leading the company’s communications and government affairs teams in Europe, the Middle East and Africa. Earlier he was press secretary to U. S. Senator Thomas J. McIntyre (D-NH) and in the Carter Administration he was special assistant and speechwriter for Health and Human Services Secretary Patricia Roberts Harris.

Mr. Kelley’s volunteer experience includes six years on the Board of Visitors of the Nelson A. Rockefeller Center for Public Policy at Dartmouth College, a nationally acclaimed institutional home for social science research, teaching and experiential learning. In that role he has sponsored and mentored undergraduate interns working for the USCRI. He taught English as a second language at a center for immigrants in Washington, D.C. and volunteers as a National Parks Service guide at Ford’s Theater.

Mr. Kelley earned an undergraduate degree from Dartmouth College and a master’s degree from the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University.

Hila Moss joined USCRI in November 2015 as a bilingual Staff Attorney with the Nuevo Comienzo, unaccompanied minor program, where she represented children in their applications for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status, asylum and family-based petitions. In March of 2019, she was promoted to Managing Attorney and implemented a cohesive management structure while obtaining new funding opportunities for pro- and low-bono legal representation of survivors of crime, trafficking, and unaccompanied minors. In April 2022, she was promoted to the Associate Director of Legal Services and expanded USCRI’s legal department to include 14 offices with nearly 40 staff members serving refugees, immigrants and paroled Afghan arrivals. In December 2022, she was promoted to Director of Legal Services and currently oversees USCRI’s legal department. She also serves as the Project Director for USCRI’s government-funded Immigration Legal Services for Afghan Arrivals (ILSAA) contract. She resides in North Carolina with her family and has a Bachelor of Arts degree in Communication Studies from Appalachian State University and a Juris Doctorate from Campbell Law School

GOVERNANCE COMMITTEE CHAIR

Regis G. McDonald is an accomplished social service executive with decades of experience in managing and developing cutting edge programs and services for youth and families involved with the child welfare, juvenile justice, child mental health and immigration systems.

Mr. McDonald at the time of his retirement was Senior Vice President for Programs at The Children’s Village in Dobbs Ferry, New York. The Children’s Village was founded in 1851 in Lower Manhattan as the New York Juvenile Asylum. Today, the Children’s Village is a nationally and internationally respected multi-service human service organization with a staff of over 1,500 and an annual budget exceeding $91M. Mr. McDonald’s work at CV positively impacted and enriched every aspect of the organization, including its work on Undoing Institutional Racism and providing shelter and staff secure care to unaccompanied immigrant children.

At the invitation of the First Lady of Guatemala Mr. McDonald participated in two Central America Regional Child Migration Forums. One in 2013 in Antigua, Guatemala and the second in 2016 in Washington, DC. He served as a member of the United States Department of Justice Interagency Working Group on Separated & Unaccompanied Children in 2014.

Mr. McDonald earned an Associate in Arts degree from Wentworth Military Academy & College. He is the recipient of the Ted Messmore Honor Graduate Award, Wentworth’s highest award. Mr. McDonald was awarded a Bachelor of Science degree from Central Missouri State College and a Master of Social Work degree from Adelphi University School of Social Work.

Sam Udani has been involved with the immigration community in the USA for most of his career spanning three decades, involving immigration politics and immigration policy and covering all manner of immigration into the USA, including refugees. He has been a tireless advocate for enlightened immigration laws for the USA since ACWIA, AC21/ACTA and continuing from then on.

Mr. Udani currently serves as the Law Publisher and CEO of ILW.COM and Immigration Daily, a position he has held for over twenty years. As Publisher, he directs all activities of the website and newspaper with over 50,000+ pages of free information on immigration law that receives 250,000 visitors per month. Under Mr. Udani’s direction ILW has conducted 600+ CLE seminars, published over two dozen immigration law books and conducted hundreds of immigration events in over a dozen countries. Earlier in his career, Mr. Udani founded an advertising agency and a small company in international trade.

A hallowed name for refugees, and generally for the entire immigration field, is Edith Lowenstein who served as Editor of Interpreter Releases, the first (and for half a century the only) periodical reporting on developments in immigration/refugees – Interpreter Releases was housed within USCRI’s predecessor entity for its formative decades. Today’s Immigration Daily is in direct descent of Interpreter Releases, Mr. Udani is always reminded of this when before Edith Lowenstein’s image in USCRI’s board room.

Kevin Bearden is an accomplished senior executive with more than 25 years of experience in strategic business growth, corporate operations and the management of large performance-based federal programs, including humanitarian solutions, cloud, cyber data analytics and intelligent automation systems.

Currently, Kevin leads the humanitarian solutions portfolio at Cherokee Federal serving as Vice President. His new organization provides influx facility wrap around and direct care services for unaccompanied children as well as refugee support services for newly arrived Afghan parolees. Mr. Bearden previously served in C-suite and other key senior executive roles at The Providencia Group (TPG), SOS International (SOSI) and General Dynamics Information Technology (GDIT). Before entering the private sector, he was a Commissioned Officer in the U.S. Army Signal Corp and served both on active duty as well as in the Army Reserves.

Kevin is very passionate about supporting underserved and vulnerable populations. He’s traveled both domestically and internationally as part of humanitarian missions assessing the plight of unaccompanied Eritrean minors along the Ethiopian border, he’s visited urban refugee processing centers in Nairobi Kenya and has overseen numerous domestic immigration programs supporting HHS’s Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), DoS’s Bureau of Populations Refugee’s and Migration (PRM) as well as DOJ’s Executive Office for Immigration and Review (EOIR). In his spare time – Kevin volunteers and mentors aspiring young men in local DC based urban education centers.

Mr. Bearden holds a Bachelor of Science in Electrical Engineering from North Carolina A&T and a Master of Science in Systems Engineering from Johns Hopkins.

AUDIT COMMITTEE CHAIR

Helen R. Kanovsky’s distinguished career in housing began with her interest in social justice. Ms. Kanovsky has served in the U.S. government, private sector and labor movement, bringing to USCRI’s Board of Directors a wealth of expertise and experience in housing across sectors.

She currently is General Counsel at the Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA), where she oversees the association’s internal legal affairs, compliance and human resources operations.

Prior to joining MBA, Ms. Kanovsky was the General Counsel of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and had served as HUD’s acting Deputy Secretary. Previously, she was General Counsel and Chief Operating Officer at the AFL-CIO Housing Investment Trust. She was the General Counsel at both GE Capital Asset Management and Skyline Financial Services. Additionally, Ms. Kanovsky worked in private practice and on Capitol Hill, where she served as Chief of Staff to Senator John Kerry.

Ms. Kanovsky is a member of the District of Columbia Bar, the American Bar Association and the Federal Bar Association. She served for three years as the Chair of the National Housing Conference. She has spent her entire career working and advocating for stable affordable housing as a human right.

Helen holds an A.B. degree in government from Cornell University and graduated Cum Laude from Harvard Law School.