Refugees Twice Over: Climate Migration...

By: Alexia Gardner, USCRI Policy Analyst, and Anum Merchant, USCRI Policy Intern Extreme weather continues to drive new large-scale displacement, with 2024 ranked among the highest years...

READ FULL STORY

Introduction

A single mother and her daughter from Cuba arrived in Mexico seeking safety. Under Mexican law, they should have received a Tarjeta de Visitante por Razones Humanitarias (TVRH), or Visitor’s Card for Humanitarian Reasons, the official document that grants asylum seekers temporary access to work, education, and basic services while their case is pending. Months passed, and the card never came. The mother was pushed into low-paid informal work, and her daughter was denied school enrollment for lack of Mexican identification, the very identification the TVRH would have provided.

With support from USCRI’s legal team in Tijuana, the family eventually obtained their cards through a court order. Most asylum seekers, however, do not. Across Mexico, thousands are being excluded from formal jobs, education, and essential services because the National Institute of Migration (INM) has effectively stopped issuing this critical document.

Mexico’s Evolving Regional Role in International Protection

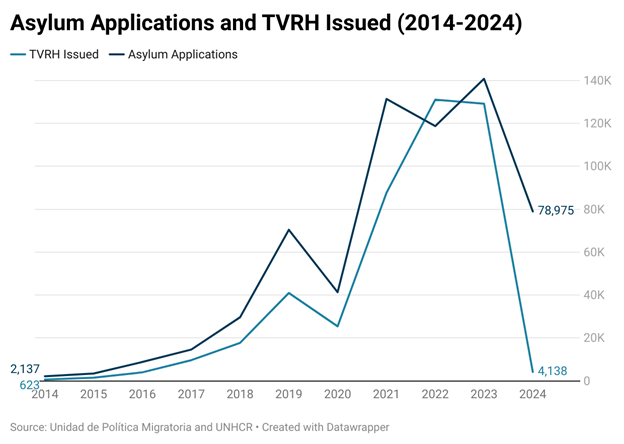

Mexico, a longstanding transit country for asylum seekers, has become a destination for migrants across the Americas in recent years. In 2014, the country received 2,137 asylum applications. That number rose to more than 130,000 in 2021 and reached a record 140,000 in 2023. That year, amid record encounters at the U.S. southern border and pressure from the U.S. Government, Mexico intensified migration enforcement and restricted access to the TVRH. In practice, the INM suspended the issuance of the TVRH for most first-time applicants.

In 2024, the INM issued 97% fewer cards than the previous year. Nearly all cards now issued are renewals rather than first-time approvals, according to Diego Ramirez, a USCRI lawyer in Tijuana. The suspension has left thousands without identification or access to formal employment, education, and essential services, violating their human rights.

Despite increased enforcement, people continue to arrive and seek asylum in Mexico. The Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR) received roughly 80,000 applications in 2024 and is on track for a similar number in 2025. UNHCR’s 2025 Protection Monitoring tool found that a growing share of the people arriving in Mexico fled violence or persecution in their country and that most identified Mexico, not the United States, as their intended destination.

As the United States restricts humanitarian entry, including through pausing asylum applications and the rollback of Temporary Protected Status for some nationalities (visit USCRI’s “Get the Latest” for more), many displaced people view Mexico as a viable option, at least temporarily. Yet, without the TVRH, they are deprived of rights guaranteed to them under the 2011 Migration Law of Mexico which places them at a greater risk of exclusion and exploitation.

What is the Visitor’s Card for Humanitarian Reasons (TVRH)?

Under Mexican migration law, the INM must issue a TVRH to foreign nationals in certain situations of vulnerability, including asylum seekers. The card grants one year of lawful stay, renewable until the asylum case concludes. It allows holders to travel within the country, obtain a Temporary Unique Population Registry Code (CURP), and access health, education, and formal employment. The card also protects them from deportation.

TVRH denial constitutes a violation of human rights and Mexican law

The INM’s refusal to issue the TVRH is both unlawful under Mexican law and violates asylum seekers’ human rights, including the rights to legal identity, work, education, and healthcare. Mexican law states that asylum seekers are entitled to receive the card while their case is pending. In practice, the INM has systematically ignored this obligation, leaving thousands in legal limbo. Denying the required document undermines these rights and puts Mexico at odds with its international treaty obligations and national law.

Since 2023, the INM has blocked new cards for most first-time applicants. The agency has continued to renew cards on a limited basis for those who already have them, but new applicants face near-total denials. When questioned, INM officials point to these few renewals as evidence of compliance, even though the agency is refusing to issue cards for first-time applicants.

To avoid denying the card, some INM offices issue a substitute document known as a constancia de trámite (proof of pending process), which merely states that a person has initiated a procedure and is not valid under Mexican law. The INM has no legal authority to issue it; it bears no official signature or seal and cannot be used as identification or for employment, banking, or access to public services. According to Ramirez, the document functions as a bureaucratic loophole: “It’s how INM washes its hands. They cannot legally refuse the card, so they give this instead.”

By withholding the card, the INM denies asylum seekers access to rights guaranteed under Mexican law, including formal employment, health care, and education. Although they are lawfully present in Mexico, the absence of documentation leaves them unprotected and exposed to the same obstacles faced by those without legal status. This violates their rights and contradicts Mexico’s own legal commitments under international human rights law. The denial of such documentation also erodes trust in the Mexican asylum system.

Obstacles faced by those without TVRH and their impact on integration and protection

For asylum seekers in Mexico, the TVRH is essential. Without it, they cannot work formally, certify their children’s schooling, obtain a driver’s license, or fully participate in the economy, including using the banking system. Nearly every interaction for asylum seekers requires the card for identification.

The most serious consequence is exclusion from the formal labor market. Employers hesitate to hire asylum seekers without a TVRH, despite their legal right to work. Because opening a bank account also requires the card, employers who pay via direct deposit have no way to compensate them. As a result, many work in the informal sector where exploitation is common and wages are lower, and where they are not covered by social security.

The economic effects are tangible. Gabriela Hernandez, director of Casa Tochan in Mexico City, described a young man who had lived independently for months and worked a steady job while he waited for his card. When the card did not arrive, his employer dismissed him, and he returned to the shelter in economic distress. In Tijuana, Diego Ramirez secured a TVRH for a client whose wife was pregnant and who received a job offer with a higher salary but could not accept it without the card. These cases highlight the necessity of the card in securing formal employment and illustrate how the card determines whether asylum seekers can achieve financial stability and self-sufficiency.

The lack of the card also disrupts access to education. To enroll in school, children must present a CURP, which is granted only with a TVRH. While some schools allow enrollment, they cannot certify completion without it, discouraging many parents from registering their children. The CURP is also required for public services such as healthcare, though hospitals must provide emergency treatment regardless of immigration status.

These barriers to employment and education hinder long-term integration. Adults face exploitation in the informal sector and economic uncertainty due to low wages, while children risk falling behind in school. Without the card’s protection from deportation, asylum seekers also face fines or extortion by authorities, even when they show proof of pending asylum applications.

Overview of legal appeals and rulings

As a result of the INM’s actions, lawyers across Mexico rely on the juicio de amparo as the only available remedy. Amparo is a constitutional mechanism that protects individuals from human rights violations committed by public authorities. Lawyers file amparos before federal judges, arguing the INM’s failure to issue the card constitutes unlawful omission. Because each ruling applies only to an individual petitioner, lawyers must file cases one by one. Achieving universal, class-wide relief through the courts is unlikely, given the legal and procedural constraints.

Applicants typically present their constancia de trámite and other evidence showing they have complied with all requirements. The INM, however, often ignores judicial orders and fails to respond until judges threaten sanctions. According to Ramirez, “There is zero openness to dialogue” on the part of the INM. Even with court rulings in favor of asylum seekers, compliance is delayed until the last possible moment.

Court orders have brought individual victories, such as the case described above in which a judge intervened to force the INM to grant a man a TVRH so he could accept a formal job offer while his wife was pregnant. Yet systemic relief remains difficult. Each amparo applies to only one person, even within the same family. Organizations have also sought recourse by filing complaints before the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH). Although the CNDH has issued recommendations, the INM dismisses them by pointing to renewal statistics as evidence that they are issuing the cards.

Cases can take up to a year to resolve, and even successful rulings do not correct pervasive and consistent institutional noncompliance. Despite efforts from lawyers and civil society, no substantive change has been achieved. As advocates note, the only strategy that forces action from the INM is sustained judicial pressure.

Beyond the humanitarian sector, the problem remains largely invisible. Few media outlets cover the suspension, and public awareness is minimal. Yet, for asylum seekers and legal advocates, it represents a crisis. The repercussions for those seeking asylum are significant and hard to fully measure.

Conclusion

The suspension of the Visitor’s Cards for Humanitarian Reasons reflects a troubling contradiction in Mexico’s asylum system. While the Government recognizes asylum seekers’ legal rights, it denies them the very document that allows them to exercise those rights. The amparo process offers individual relief but cannot replace the need for INM compliance with Mexican law. Restoring TVRH issuance is essential to uphold the rule of law, protect asylum seekers’ rights, and ensure Mexico’s commitment to humanitarian and human rights principles.

Recommendations:

For the Mexican government:

For local governments:

For civil society:

For the United States Government:

On Human Rights Day, and every day, we reaffirm that the rights of asylum seekers in Mexico are not privileges but legal obligations that the State must uphold. By refusing to issue the TVRH to thousands of people seeking protection, the INM denies them the ability to work, study, and live with dignity.

Without the reinstatement of TVRH issuance, Mexico not only violates the human rights of thousands of asylum seekers but also perpetuates their exclusion and leaves meaningful integration and protection into Mexican society out of reach.

Support USCRI’s Still Standing Campaign in Latin America and the Caribbean

USCRI’s legal work to secure Humanitarian Visitors Cards for asylum seekers is part of its Still Standing strategy, which aims to serve displaced people in Mexico, Honduras and El Salvador and focuses on four key priorities: protection, livelihoods, education and humanitarian assistance. Thus far in 2025, USCRI’s legal team in Tijuana has secured seven cards, guaranteeing access to work, education, and other basic rights for migrants.

Still Standing is a USCRI declaration of commitment to stand along immigrants, refugees, and returnees even when migration pathways falter and support systems weaken. This effort reflects USCRI’s broader mission to protect rights, advance integration, and ensure that displaced people can rebuild their lives with dignity.

Visit Still Standing to learn more about how you can join us in our mission.

By: Alexia Gardner, USCRI Policy Analyst, and Anum Merchant, USCRI Policy Intern Extreme weather continues to drive new large-scale displacement, with 2024 ranked among the highest years...

READ FULL STORY

A child who is separated from their parent or caregiver does not experience a policy decision; rather, they experience fear,...

READ FULL STORY

Our Policy and Advocacy Newsletter introduces our latest project: From the Archives. For more than a century, the U.S. Committee for Refugees and...

READ FULL STORY