TURNING PERIOD POVERTY FROM STRUGGLE...

By Firdaus Bashee - Country Director, USCRI Kenya and, Sudi Omar Noor Founder, Girl Power Action Initiative (GPAI) In...

READ FULL STORY

By: Rosalind Ghafar Rogers, PhD, LMHC, Clinical Behavioral Health Subject Matter Expert with USCRI’s Refugee Health Services in Arlington, VA

The United Nations General Assembly proclaimed November 25th as the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women and Girls which marks the launch of 16 days of activism concluding on International Human Rights Day (December 10). Observing this day and engaging in activism symbolizes the commitments and actions of citizens, communities, organizations, and governments to increase awareness, share knowledge, and mobilize efforts to ensure that women and girls, in all their diversity, live free from all types of violence.

Violence against women and girls is a global and systemic crisis. 1 in 3 women worldwide have been subjected to violence at least once in their lifetime. Worldwide, among girls ages 15 to 19, almost 1 in 4 have experienced physical and/or sexual violence, 15 million girls have experienced forced sex, and 16% of young women aged 15 to 24 have experienced physical and/or sexual violence in the past 12 months (UN Women, 2023a). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about 47% of women in the U.S. have experienced physical or sexual violence and/or stalking victimization at some point in their lifetime (Leemis et al., 2022). Racial and ethnic minority groups are disproportionately affected by intimate partner violence in the U.S. (Leemis et al., 2022). Unfortunately, research on violence against migrant and refugee women is extremely scarce, however, based on studies with this population, findings indicate high prevalence rates. Research, mainly in Europe, shows that approximately 57% of refugees have experienced sexual violence, and 76% of refugee and asylum-seeking women had been raped either in their home country or in the UK (De Schrijver et al., 2018).

Types of Violence Against Women and Girls

The UN defines violence against women and girls as “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual, or mental harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.”

Gender-based violence (GBV) is an umbrella term for harmful acts of abuse against an individual based on biological sex or gender identity, and it is rooted in gender inequality, the abuse of power, and harmful norms (UN Women, n.d.). GBV can manifest in a variety of ways including physical violence, such as assault; emotional or psychological violence, such as verbal abuse or confinement; sexual violence, such as rape, sexual harassment, and incest; socio-economic violence, such as withholding access to financial resources or forbidding employment; or harmful practices, such as child marriage and female genital mutilation.

Domestic violence (DV) is violence that occurs within a private, domestic setting, generally between individuals who are related through blood or intimacy. Intimate partner violence (IPV) is one of the manifestations of DV and refers to a pattern of coercive and abusive behaviors by an intimate partner or ex-partner to maintain power and control and causes physical, psychological, or sexual harm (UN Women, n.d.). IPV is the most common form of violence against women in war and displacement.

The effects of violence against women and girls are pervasive and powerful, with far-reaching consequences on survivors’ physical, social, and psychological wellbeing. Survivors of violence are more likely to experience higher rates of health problems, such as physical injuries, neurological disorders, eating and gastrointestinal conditions, and chronic pain and disease, among others. Violence can also result in sexual and reproductive health issues, such as sexually transmitted infections, early and unintended pregnancy, and pregnancy complications. Extreme forms of violence can result in death, with an estimated 47,000 women and girls worldwide killed by an intimate partner or other family member in 2020 (UNODC, 2021).

Violence against women is also associated with a range of mental health problems with varying degrees of severity and effects on functioning. Depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance abuse, personality disorders, psychosis, self-harm, and suicidality are all common among individuals who have experienced DV or IPV than those who have not (Oram et al., 2022). Children are also harmed by exposure to DV or IPV, which increases their risk of anxiety, depression, and poor behavioral and educational outcomes. Moreover, violence has intergenerational effects: Exposure to IPV or DV in childhood significantly increases the risk of both experiencing and perpetrating IPV or DV as an adult (Hashemi et al., 2022).

Women’s flight from their home country and the displacement, migration, and resettlement that follow, increase migrant and refugee women’s risk for IPV or DV. Displacement and migration are associated with many changes and stressors, including a disrupted social support system, language barriers, and a lack of familiarity with the host country’s legal and social systems – all of which, in turn, are likely to intensify a sense of isolation and loneliness. Research studies of IPV among migrants and refugees have consistently found a sense of isolation, lower levels of perceived social support, and a smaller social support network and/or a shift from extended family to a nuclear family structure (Family Violence Prevention Fund, 2009). Isolation due to migration may increase women’s dependency on partners and is often intensified by abusive partners’ tactics of control and threats of deportation. Research has also found that gendered social norms and roles, destabilization of traditional roles, men’s substance use, women’s separation from family, rapid and forced marriages, and higher levels of acculturation were interrelated factors that increased migrant and refugee women’s risk for IPV or DV (Njie-Carr et al., 2021).

Victims of GBV, IPV, and DV experience numerous barriers to seeking and accessing help. The abusive, manipulative, and coercive tactics that perpetrators use to devalue, isolate, and shame/humiliate, leaves victims feeling trapped, dependent, and powerless. Victims of violence are often caught in a double bind – experiencing abuse if they remain and yet potentially facing consequences if they attempt to access resources, services, and other forms of support and assistance. For migrant and refugee women, these barriers are significantly exacerbated because of immigration laws, anti-immigrant sentiments, racism, xenophobia, cultural and religious norms and values, and issues of linguistic and cultural competence among service providers. Additional barriers migrant and refugee women face include:

Addressing and ending violence against women and girls requires not only reacting to it when it happens but finding proactive and innovative solutions and multi-level and intersecting approaches to programs, services, and policies aimed at the prevention of violence against women and girls.

Awareness and Education

Raising awareness and providing education involves reshaping cultural norms or false perceptions about GBV, DV, and IPV and includes educating ourselves, our communities, and migrant and refugee populations about healthy relationships, the dynamics of abuse, and the root causes of these forms of violence.

Empower Survivors

Frontline workers and service providers, programs, and systems should use a survivor-centered and strengths-based approach that centers survivors’ voices and experiences and promotes women’s autonomy, self-worth, and their priorities.

Formal and Informal Sources of Support

Due to the many structural barriers that migrants and refugees face, many migrant and refugee survivors seek informal sources of support, such as family and/or other supports. Therefore, there is a need to improve formal, mainstream sources of support and to identify and strengthen informal support networks.

Whether through educating ourselves, raising awareness, amplifying women’s voices, investing in women’s rights organizations, being a source of compassionate support to a survivor you know, or highlighting the incredible strength, courage, and resilience of migrant and refugee women, we all have a role to play in preventing and eradicating violence against women and girls once in for all.

If you or someone you know is experiencing any type of abuse, call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233 (SAFE) or 1-800-787-3224 (TTY) for anonymous, confidential help available 24/7.

If you or someone you know is thinking about suicide or would like emotional support, call or text 988, the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline that is available 24/7. If you or someone you know is having a life-threatening emergency, please call 911.

References

De Schrijver, L., Vander Beken, T., Krahé, B., & Keygnaert, I. (2018). Prevalence of sexual violence in migrants, applicants for international protection, and refugees in Europe: a critical interpretive synthesis of the evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(9), 1979.

George, C. (2002). Hardly a leg to stand on: The civil and social rights of immigrant victims of domestic violence. Loyola University Chicago, Center for Urban Research and Learning, and Apna Ghar, Inc. Retrieved from http://loyolacurl.squarespace.com/s/AG_Hardly_a_Leg_to_Stand_On.pdf

Hashemi, L., Fanslow, J., Gulliver, P., & McIntosh, T. (2022). Intergenerational impact of violence exposure: Emotional-behavioural and school difficulties in children aged 5–17. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 771834.

Leemis, R. W., Friar, N., Khatiwada, S., Chen, M. S., Kresnow, M., Smith, S. G., Caslin, S., & Basile, K. C. (2022). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2016/2017 Report on Intimate Partner Violence. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs/NISVSReportonIPV_2022.pdf

Njie-Carr, V. P. S., Sabri, B., Messing, J. T., Suarez, C., Ward-Lasher, A., Wachter, K., Marea, C. X., & Campbell, J. (2021). Understanding intimate partner violence among immigrant and refugee women: A grounded theory analysis. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 30(6), 792–810.

Oram, S., Fisher, H. L., Minnis, H., Seedat, S., Walby, S., Hegarty, K., Rouf, K., Angenieux, C., Callard, F., Chandra, P. S., Fazel, S., Garcia-Moreno, C., Henderson, M., Howarth, E., MacMillan, H. L., Murray, L. K., Othman, S., Robotham, D., Rondon, M. B., Sweeney, A., Taggart, D., & Howard, L. M. (2022). The Lancet Psychiatry Commission on intimate partner violence and mental health: Advancing mental health services, research, and policy. The Lancet Psychiatry Commissions, 9(6), 487-524. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00008-6

UNODC. (2021). Killings of women and girls by their intimate partner or other family members: Global estimates 2020. Research and Trend Analysis Branch, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/statistics/crime/UN_BriefFem_251121.pdf

UN Women. (2023a). Facts and figures: Ending violence against women. Retrieved from https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/facts-and-figures

UN Women. (n.d.). FAQs: Types of violence against women and girls. Retrieved from https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/faqs/types-of-violence

UN Women. (2023b). Ten Ways to prevent violence against women. https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/explainer/2023/11/ten-ways-to-prevent-violence-against-women-and-girls

By Firdaus Bashee - Country Director, USCRI Kenya and, Sudi Omar Noor Founder, Girl Power Action Initiative (GPAI) In...

READ FULL STORY

To commemorate National Human Trafficking Prevention Month, USCRI, along with the University of South Carolina, Georgetown University’s Institute for the...

READ FULL STORY

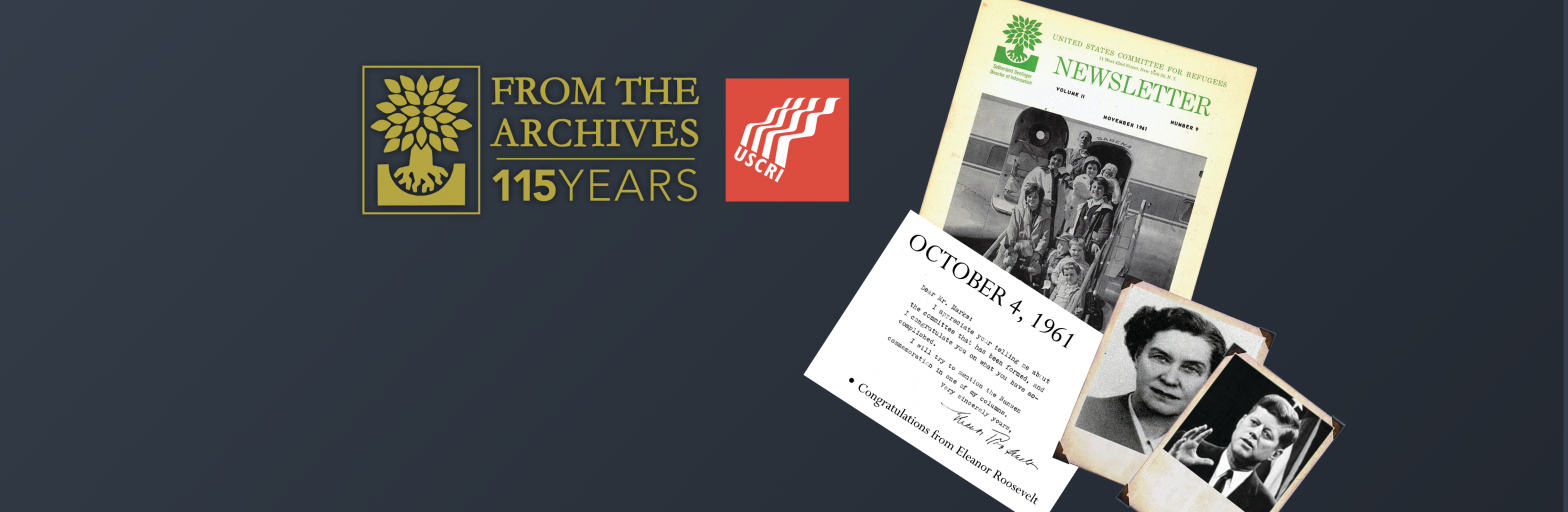

For more than a century, the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants has advocated for the rights and dignity of refugees,...

READ FULL STORY