Through My Eyes: Early Reflection...

by Sylvia Maru, Program Manager, Keep Girls Dreaming Stepping into Kakuma Refugee Camp for the first time is an...

READ FULL STORY

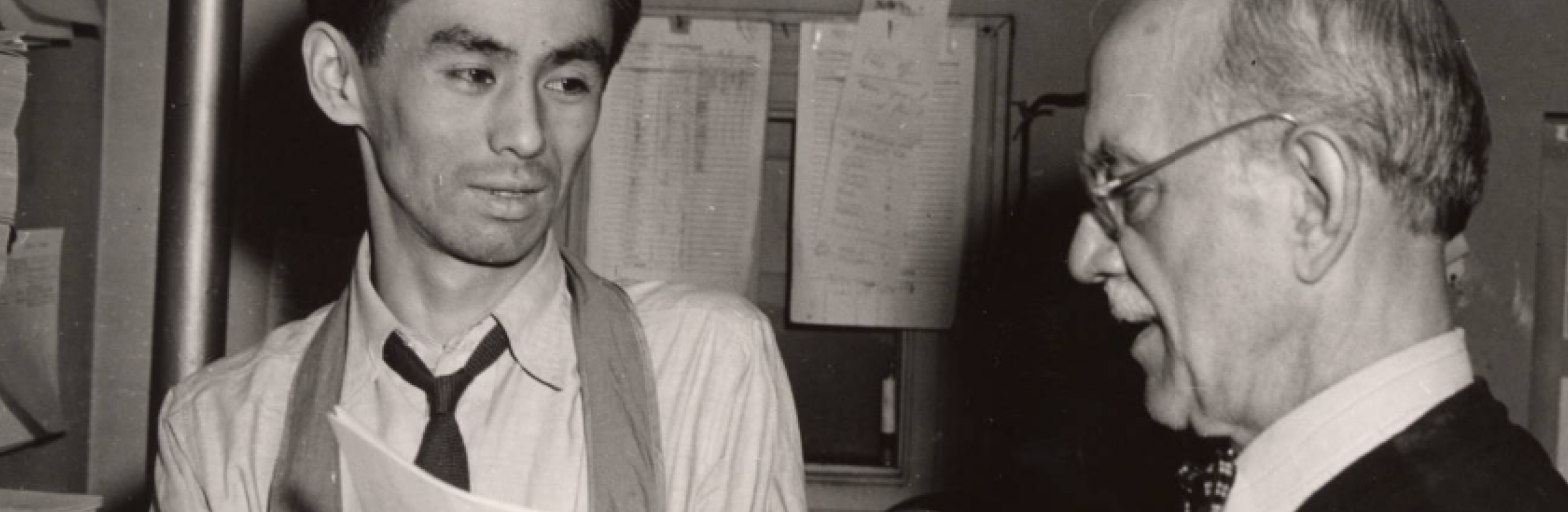

Photo: University of Minnesota Libraries, Immigration History Research Center Archives.

The Alien Enemies Act became law over 200 years ago. The Alien Registration Act was passed in 1940, when immigration and government looked starkly different. Both of these laws were passed when the country was on the brink of war with adversary nations. Yet, these outdated laws are being invoked today. In this brief, we explore how these laws harmed immigrants, racialized minorities, and U.S. citizens over the course of our nation’s history.

Alien Enemies Act

The Alien Enemies Act, 50 U.S.C. § 21 et seq., is a wartime power that authorizes detention and removal of all noncitizens over the age of 14 years of a “hostile nation or government.”

A Controversial Wartime Power

The Alien Enemies Act of 1798 was passed in a set of four laws that sought to silence criticism of the U.S. Government, led by the Federalist party, at a time when it was on the brink of war with France. The four laws are collectively known as the “Alien and Sedition Acts.” The Acts were controversial at the time and were supported by Federalists who suspiciously viewed political critics. The Federalists lost reelection in 1800 due to their efforts to chill free speech. Two of the four laws were allowed to expire, and one was repealed in 1802. The Alien Enemies Act is the only law of the four that was retained. The Alien Enemies Act was utilized again during the War of 1812 and World War I.

The Immoral Legacy of Japanese Internment

During World War II, the Act was used against people of Japanese descent, who were labeled as “alien enemies.” After the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt invoked the Act to prohibit people of Japanese descent from entering or leaving certain areas, from moving residences, and from changing occupations. A series of further restrictions culminated in Executive Order 9066, which allowed the military to exclude any person from military areas.

Although the Executive Order was racially neutral, Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt of the Western Defense Command announced curfews that applied only to people of Japanese descent. Dewitt then rounded up people of Japanese descent, including citizens and legal permanent residents, and put them in forced detention in remote areas.

Undue Deference to National Security

Fred Korematsu, a U.S. citizen, challenged the internment order. The Supreme Court, in Korematsu v. U.S., declined to review the internment order for racial discrimination and deferred to DeWitt’s assessment that internment was a “military necessity.” Korematsu was convicted of violating military orders, sentenced to probation, and interned at San Bruno, California.

In legal education, Korematsu is taught as anti-canon law, meaning that it so factually and legally flawed that it is taught to highlight the potential for manipulation and racial bias in judicial review.

When deciding Korematsu, the Supreme Court gave deference to Dewitt’s assessment—that all people of Japanese descent needed to be detained as a military necessity. But the Government failed to disclose other intelligence reports that contradicted Dewitt’s conclusion that mass internment was necessary for national security.

Justice Frank Murphy, in his dissenting opinion, was the only one to recognize that xenophobia was a cause and motivation of DeWitt’s assessment. Murphy challenged the inference that all people of Japanese descent were disloyal to the United States for the sole basis of their lineage. Murphy was the only Justice to examine the xenophobic environment of the time and the vitriol against people of Japanese descent for farming American lands and working American jobs. Years of racialization and propaganda against immigrants made the public believe that the urgency of war necessitated group condemnation, rather than individual due process.

It was not until 40 years later that the federal courts confronted the depth of their irresponsibility. In 1983, a new legal team of young, Japanese American attorneys presented a petition for a writ of “coram nobis,” or a confession of error.

A wartime commission concluded that at the time of the initial lawsuit, the Government’s attorneys suppressed substantial evidence contradicting DeWitt’s assessment. The Commission concluded that “race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership” resulted in the unjust detention of thousands of citizens, legal immigrants, and families. In light of this evidence brought to the federal courts, Fred Korematsu’s conviction was overturned. However, the original Supreme Court decision retained precedential value. Legal scholars have warned of the danger that Korematsu symbolizes: “the prospect of considerable government excess under the mantle of national security.”

In Trump v. Hawaii, a legal challenge to sweeping travel bans, Justice Roberts obliquely stated that Korematsu was overruled: “Korematsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and—to be clear—’has no place in law under the Constitution.’” But in the same opinion, the travel ban was upheld with deference to the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) claim that a sweeping ban was necessary for national security. Referencing Korematsu only highlighted the dangerous potential for courts to turn a blind eye to civil liberties when the government invokes national security.

Today

On March 15, 2025, the Administration invoked the Alien Enemies Act to deport without due process 137 Venezuelan nationals to El Salvador, where they are being held in a supermax prison. Lawsuits challenging use of the Act and the individual deportations are moving through the federal courts.

The Alien Enemies Act, when it was last used during World War II, caused generational harm and trauma to people of Japanese descent. And when it comes to judicial review of this Act, Korematsu and its progeny show us that we cannot rely on the federal courts to protect civil liberties when the Act is invoked.

Alien Registration Act

The Alien Registration Act requires all noncitizens who are in the United States for 30 days or more to register, be fingerprinted, and carry proof of registration. When the law was introduced in 1940, Europe was in the midst of brutal war against fascist governments that promoted extreme ideologies. Politicians were also hoping to counter communism, which was rising in Russia and which led to bloody civil wars before the Soviet Union was formalized.

The Alien Registration Act originally included an anti-sedition clause, which made any speech that advocated, abetted, advised, or taught the overthrow of the Government criminally unlawful. The combined Act is also known as the “Smith Act,” named after Representative Howard Smith. Rep. Smith is known for blocking civil rights legislation, including the Civil Rights Act.

Widespread Registration: 1940-1944

The registration requirement went into immediate and full force. An Alien Registration Division was created within the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), the sole governmental agency in charge of immigration at the time. The Government launched a nationwide public information campaign for registration. The Act originally included an assurance that in return for registration, deportation would be suspended if an individual proved good moral character, admissibility and eligibility to be a U.S. citizen, and that deportation would result in “serious economic detriment” to a citizen or resident family member.

In less than four years, the Alien Registration Program registered over 5.6 million noncitizens using paper records. Every noncitizen filled out the same registration form and received a universal receipt card, which attested to proof of registration, rather than note a certain immigration status. Registration facilitated the roundup and internment of people of Japanese, German, and Italian descent.

After four years of the program, the Alien Registration Division was eliminated due to the infeasibility of tracking registrations, address changes, exits, and deaths. Registration also shifted to ports of entry, and registration receipts were revoked by 1950.

When the registration portion of the Smith Act was incorporated into the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, it got rid of a major, protective aspect that made widespread registration possible in 1940-1944. It no longer included the assurance of suspending deportation for people who entered without inspection.

The Muslim Registry

After 9/11, the Department of Justice (DOJ) implemented the Nation Security Entry-Exit Registration System (NSEERS) on June 5, 2002. The program singled out nationals from 24 Muslim-majority countries and North Korea for photos, fingerprinting, and additional security scrutiny.

The program was integrated into the visa system and was utilized at points of entry, such as borders and airports. It did not require people without documentation to register, nor did it require people who were granted humanitarian protection, such as asylees and refugees, to carry proof of registration. The program was later expanded to require certain males over 16 years of age already present in the United States to “call-in” and register.

In 2011, DHS delisted all 25 countries from the program, and it removed the regulatory framework in 2016. DHS found that “NSEERS no longer provides a discernable public benefit.” Rather, NSEERS created fear and harm by facilitating racial profiling. Arab, Middle Eastern, Muslim, and South Asian men were subjected to undue interrogation and detention. Not a single terrorism-related conviction resulted from the registration program.

Registration Is Unsustainable

Scholars note that alien registration programs have frequently been called for during times of war or emergency. However, the cost and impossibility of complete registration make them politically unsustainable. Registration and carry requirements are even more complicated today. More immigration statuses exist today, such as T visas for trafficking survivors and refugee status for people fleeing persecution. Also, when individuals transition from one status to another, for example from a temporary visa to an employment-based visa, they could be technically “without status” for months in between while applications are processed.

Enforcement also brings up the problem of differentiation. When NSEERS was implemented, it caused mass fear in Arab, Muslim-majority, African, and South Asian communities, and young men were at risk of enforced disappearances on American soil.

Today

On March 12, DHS resurrected the Alien Registration Act of 1940 and set out requirements for all noncitizens, including people who are undocumented, to register and carry proof of registration. Evasion and noncompliance with carry requirements can result in fines, imprisonment, and deportation. The requirement went into effect on April 11, 2025.

Conclusion

Both the Alien Enemies Act and Alien Registration Act were passed in wartime and were abused to exact harm on racialized groups, citizens and noncitizens alike. These laws are not perennial. Rather, they are invoked as national security necessities during times of real and manufactured crisis, quickly retired when the crisis dissipates, then widely condemned by advocates and legal scholars. We have the advantage of hindsight. America should take this opportunity to reexamine the history of these laws and move toward the long-awaited step of repeal.

by Sylvia Maru, Program Manager, Keep Girls Dreaming Stepping into Kakuma Refugee Camp for the first time is an...

READ FULL STORY

Arlington, VA — [December 19, 2025] — A recent rule issued by the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) prohibits refugees, asylees, and humanitarian...

READ FULL STORY

Why Are We Asking You to Keep Eyes on Sudan? The people of Sudan are suffering a crisis escalating...

READ FULL STORY